|

Part One of Bertrand Russell's The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism (1920) comprises eight chapters under the heading 'The Present Condition of Russia' [1920]. Briefly the main points of each chapter: 1. 'What is Hoped from Bolshevism.' Russell informs us that Communism inspires people with hopes "as admirable" as those of the Sermon on the Mount. So Christians at least should be willing allies of Communist movements if they only knew their own ideals (if Russell is right that is.) But then he says that Communists hold their ideals just as fanatically as Christians and since "cruelty lurks in our instincts" and "fanaticism is a camouflage for cruelty" Communism is "likely to do as much harm" as Christianity has done. And it seems as if the tyranny of some Communist states has indeed equaled that of Christians when they have been in control of state power (and not only Christians: it seems almost all states based on religion have been just terrible and still are to this day.) Later we will see how he thinks a Communist state may avoid this pitfall although the Russians probably won't. Russell says (1920) capitalism is doomed because it is so bad, so unjust that working people will not put up with it much longer. Indeed "only ignorance and tradition" keep it going. Well. "ignorance and tradition" still seem to have a lot of steam left. The exceptional power and efficiency of the US are such that it might hold up the capitalist system another 50 years or so-- but it will be weaker and weaker and will never have the dominance it had in the 1800s, or so Russell thought. According to this the game should have been over in the 1970s. Russell may have been off by 30 years. It was possible that the world crisis ignited in 2007 would have led to a general collapse but it didn’t. The US is the mainstay of the capitalist order so if it does go down it may well take the rest of the capitalist world with it. While Russell thought that the capitalism of his day was more or less ripe for replacement he did not think the Russian form could replace it. Because he thinks Bolshevism cannot be a viable way to build socialism in the West he opposes it-- but not from the point of view of defending capitalism in any way. Bolshevism is the socialism of a backward undeveloped country with no democratic tradition. It is the right form for Russia "and does more to prevent chaos than any possible alternative government would do." The lack of personal freedoms Russell found in Russia he blames on its Tsarist past and it is that past rather than communism as such that it is to blame. A Communist party taking power in England (and by extension in the US or any other country with a democratic tradition) might not get such an irresponsible backlash as happened in Russia and would be able to be "far more tolerant." This is, I think, especially so for the US where the Communist Party advocates a form of socialism based on the Bill of Rights, although it’s unclear to me just what “Bill of Rights Socialism” is supposed entail and implies that there is something about “socialism” per se that needs qualification. Looking at the historic conditions of the Bolshevik's coming to power (the wreckage of W.W.I and the almost complete destruction of the Russian economy) Russell thinks communism can only come about through "widespread misery" and economic destruction. This seems historically to be the case-- Russia, China, Vietnam, Korea, etc. However he leaves open the possibility that communism could be established peacefully without the destruction of a country's economic life. Russell would like to see the least possible violence in the transition to socialism/ communism. However, he has a really goofy idea, based on half baked psychological notions he has developed, which is that revolutionaries find that "violence is in itself delightful" and so have no inclination to avoid it. This is too ridiculous to require further comment. As far as a peaceful transition is concerned, there is no a priori reason to reject this notion, but it would probably take place as a democratic upsurge of class conscious workers responding electorally to anti-capitalist parties once they had realized that their disintegrating economic conditions could not be halted by the traditional political system and its representatives. Next time we will look at Chapter 2: "General Characteristics" of the situation in Russia. Author

Thomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association.

0 Comments

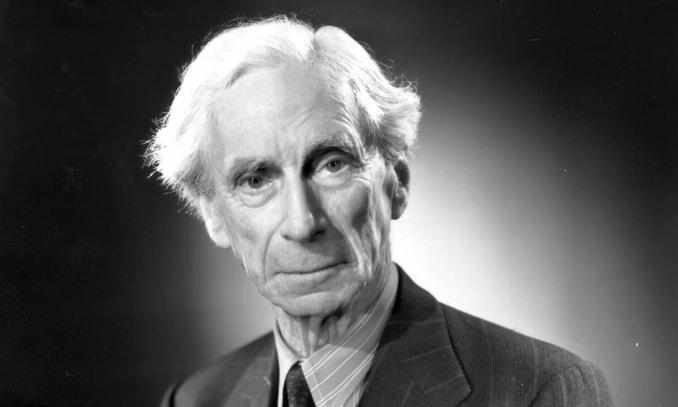

The year 2022 will see the 102nd anniversary of Bertrand Russell’s book The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism. Russell was one the twentieth century’s greatest philosophers and keenest social critics. The observations Russell made in Russia just three years after the Revolution, his impressions of Lenin (whom he interviewed) and Trotsky (no mention of Stalin), and his assessments of the future prospects of communism still make fascinating reading and since the collapse of Soviet communism seem eerily prescient. Russell has divided his book into two parts “The Present Condition of Russia” and “Bolshevik Theory.” The first part will not concern us as much as the second as it is really outdated as regards the “present condition” of Russia, although there are some observations made that are still of interest. The second is a general consideration of the philosophical outlook of Bolshevism and that still has lessons for today. I am posting this article in ten parts and will begin with the prefaces. Russell reissued the book in 1948 and in a brief preface declared that in all “major respects” he had the same view of Russian Communism as he had in 1920. I doubt if that was actually so as he says many very favorable things about the Bolsheviks in 1920 and holds contradictory attitudes about them. I think he was actually much more negative in 1948 than in 1920. Let’s begin with the original 1920 preface which was retained in the 1948 republication. Russell says Bolshevism is a radically new political movement which is a combination “of characteristics of the French Revolution with those of the rise of Islam.” This allusion to Islam will crop up again later. I note it because after the “defeat” of Communism it is radical Islam that is being touted as one of the next big threats that the US has to confront (along with Russia and China and anyone who doesn’t kowtow to U.S. hegemony). Russell says the most important fact about the Russian Revolution is the “attempt to realize socialism.” Russell is dubious about this possibility succeeding and, as we know, it ultimately failed. In the book Russell has a lot to say about this which many may still find relevant. Russell does say that "Bolshevism deserves the gratitude and admiration of all the progressive part of mankind." There are two reasons for this. First, Bolshevism stirred the hopes of humanity in such a way as to lay the foundations for the future building of socialism. Second, the future creation of a socialist world would be "improbable" but for the "splendid attempt " of the Bolsheviks. Russell uses the term "splendid attempt" because he does not think the Bolsheviks will ultimately succeed in creating a stable or desirable form of socialism in Russia. He thinks this is because Bolshevism is "an impatient philosophy" which, in Russia, as elsewhere, is attempting to create a new world order "without sufficient preparation in the opinions and feelings of ordinary men and women." Russell saw three possible trajectories that the Russia of 1920 would be faced with due to the hostility of the capitalist world. The first was DEFEAT by the capitalists, the second was VICTORY by the Bolsheviks but at the cost of "a complete loss of their ideals" followed by a "Napoleonic"regime and third, "a prolonged world war" which would destroy civilization. Well, he saw something through a glass darkly. The major capitalist assault to defeat the Bolsheviks was repelled (the Nazis) but the effort both in preparing for it and executing it did lead to a regime which many think sullied the ideals for which it stood and which history rather refers to as "Stalinist" than "Napoleonic." The strain of the second world war and cold war did finally defeat "Bolshevism" (now in quotes) and led to the demise not of civilization itself but of the new socialist civilization that the Russians had dreamed of founding. Nevertheless, Russell's views indicate that the attempt of the Bolsheviks was a noble one which will inspire future generations to struggle on for the construction of a socialist world. It is worth noting that Russell considers himself to be ideologically a political Bolshevik himself! "I criticize them only when their methods seem to involve a departure from their own ideals," he declares. This implies that Russell supports the Bolshevik ideal. This is note worthy because this book is touted as an anti-communist work! But while he shares the political idealism of Bolshevism, there is another side to it that he vehemently rejects. He thinks that they act like religious fanatics (fundamentalists) in the way they defend their basic philosophical ideals. He gives their adherence to philosophic materialism as an example. Russell says materialism "may be true" but the dogmatic way Bolsheviks proclaim it is off putting to one who thinks that it cannot be scientifically proven to be true. He writes: "This habit of militant certainty about objectively doubtful matters is one from which, since the Renaissance, the world has been gradually emerging, into that temper of constructive and fruitful skepticism which constitutes the scientific outlook." But no sooner does he say this than he basically takes it back and mitigates the charges against the Bolsheviks on this count. Speaking of the capitalist rulers in Europe and America in 1920 Russell says "there is no depth of cruelty, perfidy or brutality" that they would shrink from in order to protect capitalism and if the Bolsheviks act like religious fanatics it is the actions of the capitalist powers that "are the prime sources of the resultant evil." If that is what it takes to get rid of capitalism Russell seems to say "so be it." Anyway he hopes that when capitalism falls the fanaticism of the communists will fade away "as other fanaticisms have faded in the past." Unlike Marx who said he did not necessarily hold individuals guilty for the roles they played in the economic history of mankind, Russell is full of moral indignation when it comes to the capitalist rulers of his day. "The present holders of power are evil men, and the present manner of life is doomed." Let us hope this present state of capitalist decay is the heralding of that long awaited doom. Russell ends his preface by thanking the Russian communists "for the perfect freedom which they allowed me in my investigations." Russell had gone to Russia as part of a British delegation to assess the revolutionary situation (May-June 1920). It is extraordinary that he would have been on an officially approved delegation considering that he thought his own government was made up of "evil men." Part Two coming up. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. ArchivesHow to Read and Understand History was originally written in 1943. My copy is from a reprint put out in 1957 by Philosophical Library, Inc. Russell, one of the greatest 20th century English philosophers, was a great critic of the views on history of Hegel and Marx, let us see if his views are an improvement. Russell tells us straight away that he is only looking at history “as a pleasure,” as an enjoyable way to pass one’s free time, and that his approach is that of an “amateur.” Nevertheless, he thinks this approach will show what he has usefully derived from history and what others may also. He divides history into two parts — the large, which leads to an understanding of how the world got the way it is, and the small, which “makes us know interesting men and women, and promotes a knowledge of human nature” [supposing there is such a thing independent of culture]. He thinks we should begin the study of history not by reading about it but rather from watching “movies with explanatory talk.” I think he has very young children in mind, because even “historical” movies are more fiction than history. Russell maintains there have been only “three great ages of progress in the world”: the first being the growth of civilization in the Near East (Egypt, Babylonia), the second being Greece (from Homer to Archimedes), and the third being from the 15th century to the present. This scheme appears to be Eurocentric. Russell appears to credit “progress” or historical development to men of genius. He says the proof of this is that the Incas and the Maya never invented the wheel. But they certainly had men of “genius,” as they had monumental architecture and the Maya and others had invented writing. It doesn’t occur to Russell that inventions such as the wheel are called forth from certain needs within a culture. The Maya and the Inca did just fine without the wheel. What they needed was gunpowder to give a proper greeting to the Spanish. Russell also thinks that we would still be living at the productive level of the 18th century if “by some misfortune, a few thousand men of exceptional ability had perished in infancy.” This begs the question. Do the social conditions people find themselves in call forth their ingenuity and inventiveness, thus leading to progress, or is it all due to men of genius. Russell apparently believes in the ‘great man theory of history,’ but this theory rests on the logical fallacy I mentioned above (begging the question.) Russell does not approve of those who “desire to demonstrate some ‘philosophy’ of history,” and he singles out “Hegel, Marx, Spengler, and the interpreters of the Great Pyramid and its ‘divine message’.” When it comes to Hegel, he even maintains that his view of history “is not a whit less fantastic than the views of those who divine by the Great Pyramid.” In all fairness to Hegel, he and Russell may share more ideas about the nature of history than the latter thinks. In a nutshell, Hegel saw history as a gradual increase in human self-consciousness of freedom, finally leading to a condition where all human beings would be equally respected and their rights recognized. Hegel also appeals to empirical evidence, i.e., history itself, to justify this conclusion. The end which Hegel envisioned has had its ups and downs, but the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (part of the UN Charter) is the type of progress he had in mind, even though there must still be a long process of development for the ideals of this document to become translated into actuality. In theory, I am sure, Russell would not disagree with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, despite residual racist and misogynist opinions he might have shared with the people of his generation, not to mention latent eugenicist tendencies. For instance, he believes female behavior should be “circumscribed by prudential considerations”. Women who have been free to do as they like, i.e., women who have become rulers (“empresses regnant”) have, in the main, “murdered or imprisoned their sons, and often their husbands; almost all have had innumerable lovers” (one would think Russell might have approved of this considering his private life). “If this is what women would do if they dared,” he writes, “we ought to be thankful for social restraints.” The only example he gives is Catherine the Great. Henry VIII or Nero do not elicit similar thoughts about male behavior. We are also told that “men of supreme ability are just as congenitally different from the average as are the feeble-minded.” This is a view he shares with Nietzsche. The following opinion, however, is more in accord with what Hegel would believe. “Although,” Russell writes, “history is full of ups and downs, there is a general trend in which it is possible to feel some satisfaction; we know more than our ancestors knew, we have more command over the forces of nature [this is highly problematic since our economic system seems to be in the process of destroying us and our natural environment], we suffer less from disease and from natural cataclysms [also problematic].” He adds that “violence is now mainly organized and governmental, and it is easier to imagine ways of ending this than of ending the sporadic unplanned violence of more primitive times.” We must remember that Russell was writing in 1943 in the midst of World War II. Nevertheless, his “general trend” is a nod to progress, and for him the founding of the UN, the growth of the concept of universal rights, and the spread of social democratic ideals are all in accord with Hegelian notions. Despite his dislike of the notion of a “philosophy of history”, Russell’s “general trend” is in accord with Hegel’s outlook. Besides being a closet Hegelian, it is interesting to note that this essay also reveals a Platonic bent to Russell’s thought, and a decidedly non-Hegelian cyclical approach to history. “The greatest creative ages,” Russell writes, “are those where opinion is free, but behavior is still to some extent conventional. Ultimately, however, skepticism breaks down moral tabus, society becomes impossibly anarchic, freedom is succeeded by tyranny, and a new tight tradition is gradually built up.” What is striking about this passage, besides its mechanical way of thinking, is that it seems to be in agreement with Russell’s conservative critics. Russell, the “passionate skeptic,” was himself accused of breaking down conventional moral beliefs, and it was objected that his teachings would lead to social breakdown and anarchy, and hence he should not be teaching at the City College of New York. On the basis of the preceding passage, it appears that Russell might have even made the following statement: “It is true that I, Russell, am a skeptic, that I do think many conventional moral tabus are nonsense, and if my views are generally adopted a tyranny will replace our freedoms, since views such as mine lead to social breakdown and anarchy. Now, how about that teaching job?” To be fair, Russell realizes this problem, which he later calls, “the dilemma between freedom and discipline.” Russell needs a method to break the cycle described above, and he finds it in science, allied with what he calls “intelligence” (a rather amorphous concept). “Genuine morality,” he writes, “cannot be such as intelligence would undermine, nor does intelligence necessarily promote selfishness. It only does so when unselfishness has been inculcated for the wrong reasons, and then only so long as its purview is limited. In this respect science is a useful element in culture, for it has a stability which intelligence does not shake, and it generates an impersonal habit of mind that makes it natural to accept a social rather than a purely individual ethic.” But this cannot be right. Here are some German scientists in 1943: “Well, personal ethical considerations aside, our society has asked us to figure out how much Zyklon-B should be delivered to Auschwitz to eliminate x number of social undesirables per day, and is Zyklon-B the best chemical for the task at hand. Let us calculate together.” The above comments and considerations seem to me to point out serious difficulties with some of Russell’s ideas about the lessons one can learn from reading history the way he recommends — as a pleasurable leisure-time activity, one that assiduously avoids any attempt to formulate a philosophy of history. “The men who make up philosophies of history,” he writes, “may be dismissed as inventors of mythologies.” His two primary bug-a-boos here are Hegel and Marx. He sees only two functions for the study of history. First we can look “for comparatively small and humble generalizations such as might form a beginning of a science (as opposed to a philosophy) of history.” This is pretty arbitrary. Why not the beginning of a philosophy as well as a science? Hegel insisted that philosophy was to be pursued as a rigorous scientific procedure, just as any other discipline claiming to arrive at knowledge. Marx also praised the scientific method and claimed his ideas were scientific. The second function of history, according to Russell, is to seek “by the study of individuals … to combine the merits of drama or epic poetry with the merit of truth.” This is an Aristotelian approach. The first function “views man objectively, as the heavenly bodies are viewed by an astronomer; the other appeals to imagination.” I think it safe to say that Hegel and Marx fully agree with Russell’s first function, but would object to his second function as having no place in an objective study of the historical process. In fact, the basis of Russell’s animus towards Hegel and Marx is his opinion that they mix up his own second function with the first. I would like to conclude this brief presentation with a few remarks on Russell’s criticism of Marx’s views. After a lively survey of the development of the West and an appreciation of some of the most interesting classical historians one ought to study (Herodotus, Thucydides, Plutarch, and Gibbon), Russell comes to Marx, whom he, in another essay, considers a free thinker and compares to Robert Owen and Thomas Paine. In this essay, however, Marx is credited with founding the current interest in the economic interpretation of historical events. “Modern views,” Russell says, “as to the relation of economic facts to general culture have been profoundly affected by the theory, first explicitly stated by Marx [and Engels], that the mode of production of an age (and to a lesser degree the mode of exchange) is the ultimate cause of the character of its politics, laws, literature, philosophy, and religion.” Russell fails to mention the relations of production, a factor of prime importance for Marx and Engels. Russell then says — and this is something that Lenin would certainly have agreed with, as would all who have been influenced by the Marxist classics — that this view “is misleading if accepted as a dogma, but it is valuable if used as a means of suggesting hypothesis.” Russell adds that “It has indubitably a large measure of truth, though not so much as Marx believed.” Just what was excessive in what “Marx believed” merits its own discussion, but in Russell’s essay Marx’s faults seem to be sins of omission rather than commission. The “most important error” in Marx’s thought, according to Russell, is that “it ignores intelligence as a cause.” It is difficult to understand this objection. Russell says that “men and apes, in the same environment, have different methods of securing food: men practice agriculture, not because of some extra-human dialectic compelling them to do so, but because intelligence shows them its advantages.” Granted that Marx was trying to explain the development of human society and not ape society, the question becomes, where did this “intelligence” come from? It appears that it just fell from the sky into human beings. A little dose of Darwin is needed here, and if Russell had read and been influenced by Engels’ essay “The Role of Labor in the Transition from Ape to Man,” he would not, I think, have had such a reified notion of “intelligence.” Russell says he does not want to imply that “intelligence is something that arises spontaneously in some mystical uncaused manner.” He grants its causes are partly social, partly biological, and partly individual, and that “Mendelianism has made a beginning” into understanding its origins. My point is that Marx did not “ignore intelligence as a cause.” He did not single it out as a primary factor, because he saw it as part of the human condition that arises as a response to the evolution of the species and its interactions with the natural and social environment. Russell’s concern with “intelligence” appears to be the result of the prominence of the eugenics movement in his time and is reflected in his comment, quoted above, about the differences between the feeble-minded “average” folk and people such as himself (“of supreme ability”). How to Read and Understand History is an enjoyable introduction to some of Russell’s ideas, but although one can enjoy it, one cannot, I think, understand history from reading it. To understand history one must begin with The Communist Manifesto. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. BERTRAND RUSSELL ON MARX’S LAW OF CONCENTRATION OF CAPITALRussell thinks that “the most cardinal point” of Marx’s system is the “law of concentration of capital.” Russell gives a long quote from Chapter 32 of Das Kapital (“The Historical Tendency of Capitalist Accumulation”) which boils down to this: as capitalism develops it grows and solidifies into larger and larger companies by way of concentrating wealth as a result of competition (“One capitalist always kills many.”) As capitalism grows so does the working class which it exploits. This is a social development and the end result is the big corporations are in effect socialized industries owned by private interests. Eventually you have a small percentage of capitalists controlling the wealth of the world vs a huge gigantic population dependent on the means of production they control for their livelihoods and existence. Finally, the masses will take over the means of production themselves, since private management leads to speculation and crises affecting the whole world and billions of people, and run them in a cooperative manner to provide for human need, not private profit. This will be possible when the concentration of capital reaches such a massive scale that it becomes possible, under cooperative ownership, to provide the necessaries of life for all. Russell does see a tendency at work causing firms to become larger and larger-- but for different reasons than Marx. Marx overlooks the value of "the head work of capitalist management" because of his "glorification of manual labour." The capitalist needs time to think and be creative and this could lead to "management of all technically advanced businesses by a central authority, with no duties but to study the general conditions and the technical possibilities of the business in question." Russell, it would seem, is giving a premature argument for the central planning system of the future Soviet state.-- except the clever capitalists will be replaced by representatives of the working class. By and large, Russell sees capitalism becoming more and concentrated and concedes, except for the working class taking over, that "Marx's law seems true." Russell thinks as science advances and business technique becomes more complex and refined the great concentrated business firms and corporations and their operations will "become co-extensive with the State." There doesn't seem to be any change in class relations as businessmen will be running the show (workers are not clever enough by half.) But Russell had it backwards. He thinks monopoly concentration, that is the issue, will make businesses more profitable, and: "As soon as a business has reached this phase of development, State-management in general becomes profitable, and is likely to be brought about by the combined action of free competition and political forces." But, what we have seen, at least in the workings of American capitalism, is that "free competition" leads to economic collapse and that political forces are called upon when corporations, etc., become unprofitable and even then State-management is resisted. Of course, if the working class in the U.S. were to take over the big corporations, banks, etc., in conjunction with a working class led government, State-management would be used to rationalize the economy and provide for human needs rather than putting profits before people. Russell, of course, didn't see it that way because he didn't see a contradiction between the interests of the capitalist state and the workers. Russell does, however, make an interesting observation. The concentration of monopoly capitalism and the use of more and more machinery leads to the creation of a middle class "foremen, engineers, and skilled mechanics-- and this class destroys the increasingly sharp opposition of capitalist and proletariat on which Marx lays so much stress." This leads us to the question of the embourgeoisement of parts of the working class and also that of the adoption of false consciousness by some workers. We note that some 40% of unionized workers supported Trump in the 2020 general election (the same as supported McCain in 2008) . In any event, this is a problem for a separate paper. Interested readers should check out the article on the "aristocracy of labor" to be found in A Dictionary of Marxist Thought edited by Tom Bottomore et al. In a footnote Russell suggests that the growth of large industries leads to a socialization of production and while Marx noticed this "it does not seem to occur to him" that this could lead to a peaceful transition "to collective production." It is worth noting that Engels, in the Preface to the English Edition of Das Kapital (1887) wrote that after a lifetime of study of the English economy Marx thought that in England "the inevitable social revolution might be effected entirely by peaceful and legal means." So Russell was also wrong about this. After some really outdated comments about agriculture, Russell finally concludes that, for the reasons he has given, "Marxian Socialism, as a body of proved doctrine, must therefore be rejected." This paper has attempted to show that all the reasons given by Russell were based either on a misreading of Marx or a misinterpretation of his theories and therefore his conclusion is not logically sound and does nor follow. Next Up: Bertrand Russell on Bolshevism. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. |

Details

Archives

May 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed