|

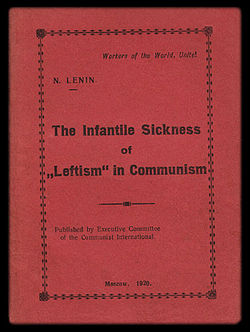

5/23/2021 V. I. Lenin: ‘Left’ Wing Communism an Infantile Disorder — Commentary and Analysis. (5/10) By: Thomas RigginsRead NowCHAPTER FIVE: Lenin on the Role of a Marxist Party in Relation to the People Lenin in 1920 made an analysis of the political conditions in Germany after the failure of the Communist (Spartacus League) uprising in 1918. The Communists had split into two rival factions. The issues facing the German Marxists were somewhat analogous to those facing the Marxist movements today especially in the industrial world. This fact makes many of Lenin's observations of the conditions in Germany relevant to the struggles of today both in advanced capitalist countries such as the U.S. (where Marxist political groupings barely make a blip on the radar screen), Europe (where Marxist parties offer viable alternatives to the status quo and have elected representatives in parliaments, local government, and sometimes as ministers in bourgeois governments (perhaps a dubious tactic), and other areas of the world as well; there is a world Marxist presence that is growing and maturing in face of the continuing decline and slow collapse of global capitalism. The setting for this chapter is Lenin's reaction to reading a pamphlet put out by opponents within the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) to the tactics taken by the leadership (a familiar scenario): "The Split in the Communist Party of Germany (The Spartacist League)". The basic position of the opposition is that the KPD leaders are opportunists seeking to work in a coalition with the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). This tactic would later be known as the United Front. This tactic is opposed by the opposition because it is demanding that the KPD stand for the creation of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat and so must reject ALL compromises with other left groups and parties and abandon parliamentarianism (elections) as well as working in the established trade unions. The KPD alone can lead the struggle and should create a new big revolutionary union under the slogan "Get out of the trade unions!" The opposition claims there are now two communist parties in Germany: the opportunist KPD "a party of leaders" and the opposition "a mass party." Lenin finds these views to be "rubbish" and "'Left-wing childishness." He then proceeds to examine the whole issue of "the masses" versus "the leaders." The "masses" are divided into "classes" and we can make only very general statements about "classes" and there are always individual cases within a given class which the generalized statement will not cover. We should be provisional and not dogmatic. In general, politically speaking, classes are led by political parties "at least in present day civilized countries" and the political leaders of a party are usually the most experienced and influential representatives of the class that any particular party represents. Lenin says this is elementary but nevertheless there seem to be some "present day civilized countries" in which the masses and the classes are not congruent -- especially where working people do not have highly developed class consciousness; i.e., in the United States, for example, most workers identify with two über-parties neither of which represent the real interests of the working class. In Europe, until recently (he means until the systemic breakdown of European culture and civilization called World War I) people were used to legal political parties and stable governments (at least in the "advanced" countries) and their political leaders were freely elected at conventions or party congresses. With the outbreak of war and revolution parties and leaders found themselves proscribed or forced to combine illegal activities with legal activities. Some leaders had to go underground, open legal party congresses could not be held or had to be held abroad. In this era of turmoil some socialists and communists began to feel uncomfortable and to complain about undemocratic leadership and a separation of the leaders from the "masses." Lenin thinks it is this confusion in the heads of those communists who have themselves little experience of the conditions of functioning underground that has led to the ultra-'Leftism' he calls an "infantile disorder." Unfortunately, this disorder has begun to spread into more experienced cadres in parties that also have experienced conditions of illegality. But in some parties, Lenin says, there really is a divergence between the leaders and the led. What accounts for this? The answer is to be found in the writings of Marx and Engels in the period 1852 to 1892 on the political developments in Britain. As the working class began to develop politically there "emerged", Lenin says, "a semi-petty-bourgeois, opportunist 'labour aristocracy'." These were those British labor leaders that went along with the bourgeoisie, compromising demands, and collaborating with the class enemy for narrow sectarian interests of their own craft or union and not working for the good of the whole class as a class. In Lenin's day this phenomenon reappeared in the Second International where opportunist leaders (Lenin calls them "traitors") worked for their own craft and became separated from the great mass of the working class-- "the lowest paid workers." Lenin says, "The revolutionary proletariat cannot be victorious unless this evil is combated, unless the opportunist, social-traitor leaders are exposed, discredited and expelled." This advice is not, I think, limited to the "revolutionary proletariat." In general militant trade unionists should keep in mind the needs of the working class as a whole and not distant themselves from supporting the struggles of other unions, non-union workers, and the lowest paid, nor should they be afraid to speak out when they see their own leaders engage in opportunist deal making with the bosses that may weaken the labor movement as a whole (sweetheart deals, no strike pledges, etc.) The mark of Left Wing Communism (LWC) is, according to Lenin, when one advocates impossible to achieve goals in a given particular situation, bucks party discipline, and drives wedges between the masses and their leaders. LWC is the flip side of opportunism and class collaboration in that they both hamper the unity of the workers in the struggle against capital. Lenin was particularly incensed by those who claimed to be against leaders "in principle." These very representatives of LWC were themselves claiming leadership positions within the working class. Lenin quotes one such ultra-leftist who wrote, "The working class cannot destroy the bourgeois state without destroying bourgeois democracy, and it cannot destroy bourgeois democracy without destroying parties." Lenin says this type of muddle-headed "Marxism" is all too prevalent amongst people claiming to be Marxists who have never studied or tried to come to grips with Marxist theory. Merely calling oneself a Marxist had become a "fashion" in Lenin's day (it's not that fashionable now when even sympathy for some aspects of Keynesianism make you a "socialist.") The idea of abolishing the party as part of the struggle against capital is ludicrous and would aid and abet the bourgeoisie. Lenin says, "From the standpoint of communism, repudiation of the Party principle means attempting to leap from the eve of capitalism's collapse, not to the lower or intermediate phase of communism, but to the higher." [I amended this quote by leaving out "in Germany" after "collapse" because I think this quote has a wider sense (Sinn)]. Parties represent the interests of classes and even after the working class comes to power it as a class and other classes as well will remain "for years" and so will leaders. The working class cannot establish socialism by just abolishing the LANDLORDS and CAPITALISTS, these classes will be easily gotten rid of (!) after a revolution-- but the PETTY-BOURGEOISIE must also be abolished and Lenin says "they CANNOT BE OUSTED or crushed: we MUST LEARN TO LIVE WITH THEM." It will take a long era of re-education to transform this class and eventually absorb it into the class conscious working class-- a process that will be "prolonged, slow, and cautious." These unheeded words go a long way in explaining the many problems that arose in both the USSR and China with respect to the peasantry. Lenin is referring not only to small business but basically to the peasantry. Advanced industrialized countries really don't have a peasant problem anymore (in this sense China is far from a really advanced country despite it phenomenal economic advances) but they do have small businesses and workers who own property (houses primarily) and/or are self-employed giving them a stake in the current economic system which Marxists seek to replace. This petty-bourgeois element, especially where there is a large peasant component, "surround the proletariat on every side with a petty-bourgeois atmosphere, which permeates and corrupts the proletariat and constantly causes among the proletariat relapses into petty-bourgeois spinelessness, disunity, individualism [the Libertarian disease and Ayn Randian brain cancer are examples], and alternating moods of exaltation and dejection." To overcome all this the workers need a party of their own with the "strictest centralisation and discipline." Without a Marxist party of this type the working class cannot carry out its PRINCIPAL ROLE and mission which is ORGANISATIONAL -- i.e., creating the necessary structures for the creation of socialism and educating the masses to that end. I must admit, looking at the conditions we have today it seems almost impossible to meet the requirements set by Lenin to carry on a successful revolution against capitalism. "The force of habit," he writes, "in millions and tens of millions is a most formidable force. Without a party of iron that has been tempered in the struggle, a party enjoying the confidence of all honest people in the class in question [the working class] , a party capable of watching and influencing the mood of the masses, such a struggle cannot be waged successfully." Anyone who weakens such a party, or questions its "iron will" (or doesn't lead in its formation one might add) is objectively an ally of the bourgeoisie and against the working people. Where do we find such a party today? In the entire Western Hemisphere only the Cuban party comes to mind. There are other parties, of course, earnestly struggling to become such parties in different countries of the hemisphere and we can only hope they achieve the confidence of the workers Lenin seems to require. The Eastern Hemisphere shows mixed results and I have no wish to try and judge which ones are doing what. But it should be noted that the movement contra austerity in some European countries may accelerate the creation of such parties where they do not yet exist and reinforce already existing militant parties. This pretty much concludes what Lenin has to say about the relation of the party and its leaders to the working masses and the errors about this relationship frequently mouthed by the ultra-left. The next chapter will try to explicate Lenin's views concerning Marxists and "reactionary" trade unions. Coming up: Chapter Six “Lenin on ‘Reactionary’ Trade Unions AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association.

0 Comments

5/16/2021 V. I. Lenin: ‘Left’ Wing Communism an Infantile Disorder — Commentary and Analysis. (4/10) By: Thomas RigginsRead NowCHAPTER FOUR: “Lenin on Anarchism and Opportunism”In chapter four of his book "'Left Wing' Communism An Infantile Disorder" Lenin describes the struggle of the Bolsheviks to combat those enemies of the working class movement who were themselves acting within that movement ostensibly in the interests of establishing socialism. Perhaps the term "enemies" is too harsh, but the factions Lenin writes about included within their ranks both opponents of the Bolshevik line (as being not historically appropriate) and hostile elements who actively collaborated with reactionary sections of the bourgeoisie. In any case, Lenin considered the main enemy of the workers to be what he called "opportunism"-- the placing of the real interests of the workers on the back burner in order to pursue temporary policies which might lead to some gains in the present, but which actually damaged the long-term interest of the workers. He was not referring to historically necessitated retreats and compromises, but to an attitude which consistently led to cooperation and capitulation to bourgeois views where matters of principal were set aside, and the long-term interests of the working class ignored. The trick, as always, is to be able to spot the difference between "opportunism" and legitimate "compromise." After 1914, the outbreak of WWI, opportunism warped into "social-chauvinism" with so-called Marxists siding with their national bourgeoisie against the bourgeoisie AND the workers of hostile nations. Lenin thought this kind of opportunism was the "principal enemy within the working-class movement." Even in 1920 it remained the number one enemy of the international working-class. And here we are, over 100 years down the road, and with the same enemy at work in the working-class. Think of right-wing labor leaders who push their unions into supporting reactionary politicians because some narrow interests have temporarily benefited, say in job creation, their own union at the expense of workers elsewhere. Lenin's old enemy is still very much alive both in the socialist and union movements. There was, however, another enemy that the Marxists had to battle. This enemy of the workers was not as well known in Lenin's day but will be recognized by everyone familiar with Marxism and the history of the 20th century worker's movement. This enemy Lenin calls PETTY-BOURGEOIS REVOLUTIONISM, a mixture of anarchism and half-baked revolutionary rhetoric. Marxist theory, Lenin maintains, has shown that the small business owner ("the petty proprietor"), independent professionals, the self-employed, and other members of the so-called "middle classes" who are situated between the large capitalist corporations and the working class, are constantly finding themselves ground down economically and subject to "a most acute and rapid deterioration" of their living conditions and "even ruin." Today this is happening throughout the capitalist world. A member of the middle class in this situation is “driven to frenzy by the horrors of capitalism is a social phenomenon which, like anarchism, is characteristic of all capitalist countries." Unfortunately, many of these people turn to right wing extremism on the one hand and to left wing groups on the other, including Marxist organizations, where they become ultra-revolutionary but are "incapable of perseverance, organization, discipline and steadfastness." Even today it is difficult for Marxist working class parties to always spot and rid themselves of this unstable element. In any case, Lenin thinks anarchism and opportunism are "two monstrosities" that go hand in hand-- the former being the punishment doled out to the working class for the sins of the latter. In the Russian context the most blatant example of petty-bourgeois revolutionism was to be found in the activities of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (neither socialist nor revolutionary in Lenin's view.) The Russian Marxists waged unremitting ideological struggle against this party (objectively a false friend of working people) over three of its most significant positions. In the first place the SRs would undertake political action without bothering to fully inform themselves of the issues, the class forces at work, and what the objective alignment of forces was. [This reminds me of a small Trotskyist party whose members once told me that Cuba had betrayed the Revolution by not attacking the U.S. Navy when Grenada was invaded by Reagan.] In the second place, the SRs engaged in personal acts of individual terrorism and political assassination which they considered to be very "Left" and very "revolutionary" actions but which the "Marxists emphatically rejected." Finally, the SRs criticized the German Social Democrats for minor opportunistic errors while they themselves were engaged in opportunistic activities far more serious than those of the Germans. With respect to the second objection to the SRs-- i.e.,"individual terrorism", Lenin does not say that Marxists are against "individual terrorism" per se or for any "moral" reason but reject it "only on grounds of expediency." In fact, he approvingly notes that Plekhanov ("when he was a marxist") had "laughed to scorn" those who "on principle" were opposed to "the terror of the Great French Revolution, or, in general, the terror employed by a victorious revolutionary party which is besieged by the bourgeoisie of the whole world." The "expediency" of terrorism is still highly contentious today, but it is safe to say that who is or is not a "terrorist" seems to be determined by which side of the barricades the one making the judgement is standing. I will make no mention of the phony "War on Terrorism" being waged by the "bourgeoisie of the whole world" against the workers and peasants of the non-industrialized world by means of drones, air raids, mercenaries, apartheid walls, and military intervention and occupation. Lenin, by the way, points out that the Russian Marxists had been proven correct in holding the position that the REVOLUTIONARY wing of German Social Democracy up to 1913 (and its traditions now carried on by the Russian Marxists) "CAME CLOSEST to being the party the revolutionary proletariat needs in order to achieve victory." [Where is the "revolutionary proletariat today”? Will the present ongoing decline of the capitalist world order regenerate it?] Now, Lenin says in 1920, it is obvious that of all the Western socialist parties, after the Great War, the revolutionary German Social Democrats have the best leaders. He is referring to the Spartacists (not to be confused with the petty-bourgeois Trotskyist sect in the U.S.) and the "Left, proletarian wing of the Independent Social-Democratic Party of Germany". [This Left consisted of the Spartacists who had joined the moderate Independents, but later (1918) broke away and became the Communist Party of Germany.] With respect to the anarchists, Lenin says the whole period from the Paris Commune to the founding of Soviet Russia proves that the Marxist critique of this group was correct. However, the demise of the Soviet Union will no doubt give a new lease of life to this ideological dead end. Lenin does, incidentally, give the anarchists credit for pointing out the opportunistic positions of the Western Marxists on the question of the state. On this question Lenin refers his readers to his book "The State and Revolution" [a work, I fear, that will not cheer the hearts of many who call themselves "Marxists" today.] Lenin now turns his attention to discussing two major struggles that were carried on within the Bolshevik movement against the "Left" Bolsheviks (actually they were left deviationists) namely, the 1908 question of participating in the Duma and the 1918 struggle around the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The problem in 1908 was that the "Left" Marxists mechanically applied the correct tactics of 1905 when the party called for a boycott of the Duma (it was completely controlled by the Tsar and was swept away by the 1905 revolution) to the situation of 1908 where the duma was not totally subservient to the Tsar and the Bolshevik delegates could openly work to influence events and educate the masses politically. The same was true of the reactionary trade unions and other mass associations. In 1905 the boycott was correct "not because non-participation in reactionary parliaments is correct in general, but because we accurately appraised the objective situation" -- that an uprising was about to occur. There was no uprising on the horizon in 1908 after the 1905 revolution had been put down so the same tactics would have been out of place. In fact, the party was in error by continuing to boycott the Duma in 1906 but corrected itself in 1908 and was correct in expelling the "Left" Marxists when they refused to see that new tactics were called for. The 1905 boycott helped the Party and the masses learn valuable lessons regarding the rejection of legal forms of opposition such as parliamentarianism but it is "highly erroneous to apply this experience blindly, imitatively and uncritically to OTHER conditions and OTHER situations." Looking back at the period from 1908 to 1914, Lenin remarks that the party would never have been able to educate and lead the masses had it not changed its tactics and engaged in legal activities even in the most reactionary institutions set up by the Tsar. Although the "Left" Bolsheviks were expelled from the party in 1908 for opposing participation in the ultra-reactionary Duma (parliament) as well as other legal organizations approved by the Tsar (unions, cooperative societies, etc.,) Lenin says they were still basically good Marxists, as they recognized their errors and corrected them, and were by 1920 again members of the Communist Party and good revolutionaries. Incidentally, Lenin in a footnote observes that "It is not he who makes no mistakes that is intelligent. There are no such men, nor can there be. It is he whose errors are not very grave and who is able to rectify them easily and quickly that is intelligent." In 1918, with respect to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk [which required the Soviets to surrender large areas to the Germans in order to get peace (and a breathing spell)] the "Left" Communist "faction" again erred but it did not lead to a split as their leaders (Radek and Bukharin) admitted their mistake in opposing the treaty in the same year. They considered the treaty to be a compromise "with imperialism" and thus antithetical to the revolution and to the working masses. Lenin agreed that it was definitely a compromise but one that "HAD TO BE MADE." Lenin would become chafed when western "Marxist" opportunists would use the example of Brest-Litovsk to justify the unprincipled compromises they were making with the bourgeoisie in their own countries. He would compare the compromise over the treaty with the compromise a person makes with a bandit who waylays his car and threatens to shoot the occupants if they don't cooperate. That is the position the Communists found themselves in. The western opportunists (Kautsky, Bauer, Adler, Renaudel, Longuet, the Fabians, British Independents and Labourites) actually made deals with their bourgeoisies against their own workers which amounted to being "ACCOMPLICES IN BANDITRY." Lenin's point is that there are some compromises forced on the masses against their will due to the balance of power at a particular time, and then there are some that are not really forced on the masses but made by leaders for their own interests and personal or political advantages. A true Communist must be able to spot the difference and fight against the latter while explaining to the masses the necessity of the former. "However, anyone who is out to think up for the workers some kind of recipe that will provide them with cut-and dried solutions for all contingencies, or promises that the policy of the revolutionary proletariat will never come up against difficult or complex situations is simply a charlatan." To make sure he is not misunderstood Lenin proposes "several fundamental rules" to be used to distinguish principled from unprincipled compromises. One can spot the former if the leaders and party advocate internationalism and reject "defense of country" in international conflicts (i.e., reject support of their own bourgeoisie against the bourgeoisie of other countries, which support actually means not supporting their own workers and the workers of other countries.) This should also involve advocating universal peace between all countries. It should also support the revolutionary efforts to overthrow bourgeois and feudal governments by workers and peasants wherever they rise up in revolt. [Lenin refers to the German Revolution specifically but his logic, I think, extends to all revolutionary movements led by the working class.] As for the latter, the opportunists, they can be recognized by their "defense of country" and justification of its military actions (or lack of serious struggle against it-- which amounts to the same thing.) Another sign of unprincipled actions is "entering into a coalition with the bourgeoisie of THEIR OWN country" in its struggle to prevail over foreign countries; they thus become "ACCOMPLICES in imperialist banditry." It is on this note that Lenin ends chapter four of "Left Wing Communism”. I must stress that the context of Lenin's thought is conditioned by the presence in Russia and in large segments of the European and International working class of a revolutionary fervor gripping millions of working people. The question for us is how to adapt Lenin's views to the present pre-revolutionary outlook of millions of people who are finding themselves being crushed by the slowly spreading decline and fall of the world capitalist system as we have known it since the end of WWII. What are we to do if we don't have on hand a revolutionary proletariat? NEXT UP: Chapter Five “Lenin on the Role of a Marxist Party in Relation to the People” AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. 5/9/2021 V. I. Lenin: ‘Left’ Wing Communism an Infantile Disorder — Commentary and Analysis. (3/10) By: Thomas RigginsRead NowCHAPTER THREE: Principal Stages In The History of Bolshevism 1905-1917 and their Relevance TodayLenin, in his book "'Left Wing' Communism An Infantile Disorder," written in 1920, maintains that there are lessons from the Russian Revolution that may be of more general interest than to Russia alone. That was 101 years ago. The world of the early twenty-first century is one dominated by global financial capital and effectively controlled by a few advanced capitalist economic powers and at least one “socialist-market” economic power who (with few exceptions) lord it over the majority of the world's population dwelling in underdeveloped and super exploited regions. Trying to find what those lessons might be today may be more difficult than finding them was in 1920. In explaining the background of the Russian Revolution and its lessons Lenin, in Chapter Three of "Left-Wing" Communism, discusses the history of Bolshevism from 1903 until the October Revolution in 1917. Let's look at this chapter to see if there are any lessons for today or to see if it is just a record of what Lenin elsewhere calls the "historical peculiarities of Russia." Lenin divides Bolshevik history into six stages which I shall briefly review. First is the period 1903-1905 "preparation for the revolution." This was a period when the three main classes of Russian society all sensed that a revolution was in the air and contended over the tactics to engage in and what sort of program should be advanced. The classes he mentions are the bourgeoisie (the liberals), the petty bourgeoisie (democratic forces calling themselves social democrats or social revolutionaries) and the working class (the authentic revolutionary forces). The classes grouped around the Czar had evidently already been eclipsed by the three "main" classes as Lenin doesn't mention them (although many of the liberals supported the idea of a "constitutional" monarchy). He does say, however, that besides the three main classes there were "intermediate, transitional or half-hearted forms." Well, even with the economic crisis the world was faced with beginning in 2008, whose working class could be considered authentically revolutionary today? There are some glimmers of revolutionary class consciousness in Europe (Greece for example), in the Third World there are some workers and Communist/ Socialist movements that are actively fighting the capitalist system in one way or another (Nepal, parts of India), and Latin America was beginning to seriously challenge US dominance. US workers haven't even got a labor party going for themselves yet and divide their votes, along with the petty bourgeoisie (which many workers think they are part of, calling themselves "middle class" ) between the two major parties of the bourgeoisie. As for the smell of revolution in the air, it is undetectable at the moment (perhaps masked by greenhouse gases). One gets, however, a whiff of fascism. In the advanced capitalist world there is not much evidence of the effects of this stage of Bolshevik history. However, there is something analogous that has been going on in Europe and elsewhere. All over the world people have been organizing and educating themselves to fight back against the corporations that have been attacking their environments and way of life. Big oil, and coal, and natural gas are increasingly finding resistance to their plans to exploit and pollute. Austerity is also being more and more rejected by the masses as a solution to the economic problems the bourgeoisie has brought upon the world. Workers in the US are beginning to wake up and fight back against the ultra-right (but this is still a very preliminary awakening.) The people may not be studying the history of Bolshevism at this point, but exploitation and oppression breeds opposition and so there is at least a family resemblance between what Lenin is writing about in the period 1903-1905 in Russia and today. The second period, " the years of revolution", is that of 1905-1907. This is the period of the birth of the first Soviets in Russia. One would be hard pressed to find anything comparable going on today in the advanced capitalist world. However, the Occupy Wall Street movement in the U.S. and similar movements in Europe and the Near East, the so called "Arab Spring''-- where not contaminated by imperialist intrigue-- were perhaps fetal developments of future Soviets or Soviet like institutions. While Lenin generally eschewed reliance on "spontaneity" as the motive force of revolutionary progress, he does say, "The Soviet form of organization came into being in the spontaneous development of the struggle." This two year period was marked by a general uprising, a revolutionary upsurge against the Russian ruling class and government. This type of "spontaneous development" does not appear to be on the horizon in the U.S. but is detectable to some extent in the poorer areas of the E.U. and, as the continued decline of the capitalist system now under way, becomes more and more intolerable for the general populations of these countries, we can expect to see the birth of revolutionary organizations analogous to those described by Lenin in LWC. This will be a period of "The alteration of parliamentary and non-parliamentary forms of struggle, of the tactics of boycotting parliament and that of the participating in parliament, of legal and illegal forms of struggle, and likewise their interrelations and connections" and all this will be "marked by an extraordinary wealth of content." This will also be the period when the working class will emerge as the main leading revolutionary force and the "vacillating and unstable" middle classes will have to submit to its leadership for meaningful change to be brought about. The coming period will give the Communist parties and their allies an opportunity to again become the leading elements within the working class and society as a whole, which if they fail to seize it will lead to their replacement by new organizational forms of struggle. These next few years will be a "dress rehearsal" for even greater struggles to come. The next period in the development of Bolshevism Lenin called the years of reaction (1907-1910). This period is really specific to Russia as we today are still on the cusp of a serious revolutionary outbreak analogous to 1905 so we don't have a current "years of reaction" against a socialist revolutionary movement to worry about. It would amount to putting the cart before the horse to discuss the reaction to a revolutionary outbreak that has not yet happened. In the US we have a move to recreate FDR era capitalist reforms to prop up the system that some leftists are falling all over themselves to support. Nevertheless some comments by Lenin in this section are of universal application at any stage of a revolutionary struggle. One of which is "that victory is impossible unless one has learned how to attack and retreat properly." Underestimating the strength of the enemy and overestimating your own has led to many a defeat in the workers movement-- often due to a pigheaded "no compromise" attitude. In periods of reaction those who can correctly gage the balance of forces are the ones who will ultimately prevail. During the 1907 - 1910 period the Bolsheviks emerged as the strongest party on the left "because they ruthlessly exposed and expelled the revolutionary phrase-mongers, those who did not wish to understand that one had to retreat, that one had to know how to retreat, and that one had absolutely to learn how to work legally in the most reactionary of parliaments, in the most reactionary of trade unions, co-operative and insurance societies and similar organizations." Understanding this explains the positions adopted by some Marxist groups in the U.S. under the ultra-reactionary period ushered in by the regime of George W. Bush. An advance to the rear in order to advance to the front later in US military lingo. The reactionary neofascist four years of the Trump administration has reinforced this tactic on the left. According to Lenin the years of reaction were followed by the years of revival (1910-1914). The revival started off slowly but speeded up because of two factors. One was the "Lena events of 1912." Lenin is referring to a massacre of workers in the Lena gold fields in Irkutsk by Tsarist troops which outraged Russian public opinion. The second factor was the exposure of the Mensheviks as "bourgeois agents." This needs some clarification. It is not the case that the Mensheviks were consciously working against the interests of the Russian workers and peasants. In their own minds they thought they were furthering a reform program that had the most realistic chances for bringing about the changes which would most help the Russian masses. How then can Lenin call them "bourgeois agents?" Lenin's rationale is that the Bolshevik program aims at the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and the creation of a workers' and peasant's state led by the working class. The Russian bourgeoisie is fighting tooth and nail, as are the Tsarists, against the Bolsheviks and seek to destroy their movement. But the attitude of the bourgeoisie towards the Mensheviks is quite different. The role of the Mensheviks, as also anti- Bolshevik (and thus for Lenin against the true interests of the workers and peasants) "was clearly realized by the entire bourgeoisie after 1905, and whom the bourgeoisie therefore supported in a thousand ways." As a result of the consciousness raising due to the Lena events and the realization of the role of the Mensheviks this period saw the growing empowerment of the Bolsheviks with the Russian masses, which was the result of their following "the correct tactics of combining illegal work with the utilization of 'legal opportunities,' which they made a point of doing." Note that in modern bourgeois democracies "legal" and "illegal" have different connotations than in nondemocratic dictatorial societies such as Tsarist Russia. The next stage is that of the "First Imperialist World War (1914-17)." It is interesting that Lenin is calling the The Great War (as it was called up to 1939) the first of its kind as if foreseeing the bloody history of the coming decades (although Charles Repington, a British war correspondent and officer, published a book in 1920 entitled “The First World War)”. This destructive war, one of the fruits of the vaunted capitalist system, brought about the death of millions and a redistribution of markets among the victorious capitalists at the expense of their rivals. The world socialist movement, supposedly united in opposition to the war which many saw coming, split when it actually broke out into those parties who supported "their" governments (who were labeled "social chauvinists" by Lenin) and those who actively opposed the war on the grounds of internationalism (workers of the world should be united against their exploiters not fighting each other for the greater glory of their "own" national bourgeoisie.) The Bolshevik stance was clear-- they opposed the war and actively agitated against supporting it among the people. This anti-war position became extremely popular amongst the majority of workers and peasants who were used as cannon fodder by the reactionary bourgeoisie. Lenin credits the adoption of this principled position, and the exposure of the social chauvinism of those who betrayed the principles of the international socialist movement as one of the main "reasons why Bolshevism was able to achieve victory in 1917-20." We come now to the last of Lenin's six stages: "The second revolution in Russia (February to October 1917)." In February 1917 the bourgeoisie overthrew the moribund and useless Tsarist regime and instituted a democratic bourgeois republic freer, Lenin says, "than any other country in the world." This Provisional government was overthrown in the October Revolution by the Bolsheviks. What went wrong with the government of the "freest country in the world"? The government was dominated by the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries (the SRs were a party basically representing peasant interests and petty-bourgeois socialists-- it was non, but not anti-, Marxist). Their weakness, according to Lenin, was their slavish (no pun intended) following of the discredited ideas of the social chauvinists of the Second International, called by Lenin "the ministerialists and other opportunist riffraff." The ministerialists were those so-called "socialists" who accepted portfolios in governments controlled by the reactionary bourgeoisie; this was considered rank opportunism by Lenin and the Bolsheviks, a case of what might be called right-wing socialism an infantile disorder. European workers should know all about these sorts of "socialists." The western socialists engaging in these opportunistic tendencies were merely repeating in the West the tactics that so discredited the Mensheviks in Russia from 1905 on. "As history would have it, the opportunists of a backward country became the forerunners of the opportunists in a number of advanced countries." Granted that the concept of "opportunism" is complex-- one person's "opportunist" is another person's "realist" -- I think Lenin uses the term to describe those who abandon principled Marxist positions to adopt positions fundamentally at odds with the long term interests of the working class because they sought temporary gains for themselves and their allies. They confuse, consciously or unconsciously, the strategic aims of Marxism with the tactical aims of the moment and mistake means for ends. Lenin ends this chapter of LWC by pointing out that the reason "the heroes of the Second International [Lenin lists Scheidemann, Noske, Kautsky, Hilferding, Renner, Austerlitz, Bauer, Adler, Turati and Longuet, and besides throws in the Fabians, Mensheviks, etc.-- characters we shall meet later] have all gone bankrupt and have disgraced themselves " is due to their inability to understand "the significance of the role of the Soviets and Soviet rule." The Soviets were councils of workers and peasants that came together to replace the bourgeois government not to submit to it and which combined both legislative and executive functions in one body. The Soviets did not represent the bourgeois concept of the "separation of powers" [for better or worse] and Lenin and the Bolsheviks saw them as a higher form of democracy (actually as an expression of the dictatorship of the proletariat) than bourgeois parliamentary democracy. The aforementioned opportunists, Lenin said, were all "slaves to the prejudices of petty-bourgeois democracy." For this reason they could not lead a successful proletarian revolution while the Bolsheviks could-- and did. Lenin concludes that the Soviet form of government is rapidly spreading throughout the world to the workers of all countries. "Experience," Lenin says, "has proved that, on certain very important questions of the proletarian revolution [he means the establishment of Soviets], ALL countries will inevitably have to do what Russia has done." Where are the Soviets today? If Lenin is right there will be no getting rid of capitalism without them-- or at least of getting rid of it by a working class revolution. Are there any viable alternatives to "petty-bourgeois democracy" on the horizon? If not, then, considering the fate of the Soviet Union, were the "opportunists" after all just "realists"? These are the questions to be answered as the struggle against the current capitalist crisis deepens and advances. Next Up: CHAPTER FOUR: Lenin on Anarchism and Opportunism AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. 5/2/2021 V. I. Lenin: ‘Left’ Wing Communism an Infantile Disorder — Commentary and Analysis. (2/10) By: Thomas RigginsRead NowChapter Two - The Russian Revolution: An Essential Condition For SuccessIn the second chapter of his 1920 work "Left Wing" Communism an Infantile Disorder, Lenin discusses what he considers to have been an essential condition for the victory of the Bolsheviks. My question is: is the Bolshevik model still viable and does it apply across the board to all societies transitioning from capitalism to socialism? Certainly Lenin is correct when he says that the revolution would not have lasted (i.e., would have collapsed in a month or two) did it not have "the fullest and unreserved support from the entire mass of the working class." I don't think any successful socialist revolution (i.e., peaceful or non-peaceful transition to socialism) can take place without the level of support Lenin says was accorded to the Bolsheviks by the Russian working people. But, this support would not have been enough, Lenin says, without a party subject to "the most rigorous and truly iron discipline." So the Russian formula was Mass Support + Iron Party = Socialist Revolution [MS +IP = SR]. But can different parties have different amounts of "iron"? This is an important formula because another way of expressing it is MS + IP = DP where DP stands for "dictatorship of the proletariat" which, Lenin says, is "necessary." Why does he think the DP is "necessary?" He gives the following five reasons. First, the capitalists are more powerful, as a class, than the workers. Second, capitalist resistance against the workers increases (Lenin says "tenfold") after they lose political power. Third, the capitalist class will get the support of the international capitalist class in its efforts to overthrow the revolution--[ this material support will be much greater than the moral support the workers will get]. Fourth, Russia has a great number of small producers and middle class elements who BY FORCE OF HABIT think in terms of capitalist ideology regardless of what their social interests might be [What's the Matter With Ukraine?] Finally, besides Russia, small-scale production is a world wide phenomenon and wherever it exists it "ENGENDERS capitalism and the bourgeoisie continuously, daily, hourly, spontaneously and on a mass scale." Because of these five conditions Lenin says the DP is absolutely necessary because not only during, but after the revolution, the working people find themselves in a "life-and-death-struggle" with the bourgeoisie and victory is not possible without it (at least in Russian conditions which are the conditions he is presently discussing: whether this is a general rule for all revolutions is another question.) Lenin himself says that the Russian experience shows that their revolution, which he seems to equate with the DP-- i.e., the revolution = "the victorious dictatorship of the proletariat"-- could not have happened without "absolute centralization and discipline of the proletariat" and this is obvious even to "those who are incapable of thinking." Is this one of the lessons of the Russian Revolution that is applicable to "all" socialist revolutions? Lenin says we should ask ourselves how was it possible for the Bolsheviks to gain the loyalty of the mass of Russian workers? There were three factors that made this possible. First, there was a VANGUARD party with advanced class consciousness which could LEAD the working people in the right political direction. Second, this vanguard was able to in effect MERGE in a way with the masses of the working people-- not only the proletariat (industrial workers in factories and other areas of capitalist production) "BUT ALSO WITH THE NON-PROLETARIAN masses of working people." Third, that the working masses, from their own daily life experiences, saw and understood that the POLITICAL LINE of the leadership of the vanguard was correct. The correct political line cannot be achieved without a correct revolutionary theory, according to Lenin. This theory is not a dogma but has to be tested in the practice of a MASS revolutionary movement. Without these three factors in operation all attempts to get the working masses to follow your line and be "disciplined" in the struggle amount to "phrase-mongering and clowning." So, the revolution was successful and the DP was instituted in Russia due to the fact that the Bolshevik party was able to discipline the working class and lead it to victory. Can the methods of the Bolshevik party be generalized and applied to other countries and revolutionary movements? Many revolutionaries have thought so and attempted to do so but Lenin himself says that the Bolsheviks succeeded "due simply to a number of historical peculiarities of Russia." This does not seem to be a firm basis for emulation. What can other countries and movements learn from the Russian revolution? Well, it can't be copied ("historical peculiarities") but two great lessons have been passed on from it. One is the centrality of Marxist thought-- "the only correct revolutionary theory" according to Lenin-- and the other is the necessity of correctly applying this theory through years of struggle and adaptation to the "historical peculiarities" of each individual and particular country and movement. This second requirement is the most perilous as the temptation will always be there to allow temporary and accidental "historical peculiarities" to mask the actual historical forces at work and thus lead to incorrect revisions of Marxist theory resulting in "phrase-mongering and clowning." This is why international meetings of revolutionary parties are so important-- to keep individual parties from isolating themselves from the world movement. Coming up: CHAPTER THREE: Principal Stages In The History of Bolshevism 1905-1917 and their Relevance Today AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. 4/25/2021 V. I. Lenin: ‘Left’ Wing Communism an Infantile Disorder — Commentary and Analysis. (1/10) By: Thomas RigginsRead NowChapter 1 - The Russian Revolution TodayThis is a commentary and analysis of all ten chapters of Lenin's work. It is an attempt to both present Lenin's views and to update them to conform with the level of revolutionary activity in our own time period in the early years of the 21st century. The success or failure of this attempt I leave to the discretion of the reader. In 1920 Lenin expressed his views on the international significance of the Russian Revolution [Chapter 1 of "Left Wing Communism an Infantile Disorder”]. A lot of water has gone under the bridge in the last 101 years, are any of Lenin's views on this issue relevant today? Well, there is a big problem with this chapter. Lenin is still waiting for a revolution in the advanced countries to come to the aid of the Russian Revolution. Despite the backwardness of Russia Lenin thinks that, after three years of revolution, there are some fundamental features of the revolution that are not local, national, or Russian and therefore will be of interest to revolutionaries in the advanced countries. He says that "certain fundamental features" of the Russian Revolution have significance for "the international validity or the historical inevitability of a repetition, on an international scale, of what has taken place" in Russia. What can he be talking about? First, he is going to try and be realistic and admits the we should not have an exaggerated view of the significance of Russian features since once the Revolution spreads to the advanced countries Russia will most likely "cease to be the model and will once again become a backward country." Second, taking the long view, since not only did no advanced country have a revolution, but the Russian model as such became defunct some seventy one years later (perhaps ultimately as a consequence) what were the features that Lenin thought had international application? Note he doesn't mention all of these features in this chapter-- he saves them for later in the work-- but we can survey his basic rationale for holding some of the Russian features to be of universal interest. It is difficult today to accept the primary thesis of this chapter: which is "it is the Russian model that reveals to ALL countries something-- and something highly significant-- of their near and inevitable future." This sentence needs revision. The "near" has to be removed and the "inevitable" is too deterministic and has to go as well-- replaced perhaps by "possible." The "ALL" is too sweeping so it will be replaced by "some." We don't need the parenthetical statement either. So we come up with "it is the Russian model that reveals to some countries something of their possible future." While it was perfectly natural for Lenin in 1920 to be all hopped up and enthusiastic about the Revolution, it is this revised thesis which I think is actually correct and that can be defended even today and will prove to be the key to a contemporary understanding of Lenin's "Left- Wing Communism" and the enduring significance of the Russian Revolution. There is a second thesis Lenin puts forth in this chapter which has to be abandoned all together, it is that the international working class has an advanced segment that, by means of a "revolutionary class instinct" (not by a conscious reasoning process) understands his first (unrevised) thesis. The most we could grant to this idea today is that there are advanced segments in the international working class but their ideas are not instinctual, they are the result of both their life-conditions (practice) and education and study of working class history and the nature of the world economy (theory). It is also the case that "advanced" workers are not all of one mind. Workers may understand intuitively (instinctively) that they are being screwed by the boss-- but that is not a sufficient basis on which to build a revolutionary movement. What evidence did Lenin have on hand for these theses? First the achievements of the revolution itself made him unduly optimistic at the time of the writing of this work. Second, he was impressed by rereading an old article in “Iskra” (from 1902) by his one time nemesis the Renegade Kautsky. The article, "The Slavs and Revolution", penned by Kautsky in his pre-renegade days, made several points that impressed Lenin as being highly relevant. Here are three sentences from Kautsky's article which must have struck Lenin as prescient. "At the present time it would seem that not only have the Slavs entered the ranks of the revolutionary nations, but that the center of revolutionary thought and revolutionary action is shifting more and more to the Slavs." What a difference a century makes! No one today would think of the Slavs as a center of revolutionary thought or action. They may have made a heroic effort in the last century but that effort ultimately failed. "The new century has begun with events which suggest the idea that we are approaching a further shift of the revolutionary centre, namely to Russia." That turned out to be correct but was unsustainable. Finally, after noting that in the revolutionary actions of 1848 "the Slavs were a killing frost which blighted the flowers of the people's spring" [the role played today by the Americans], Kautsky concludes, "Perhaps they are now destined to be the storm that will break the ice of reaction and irresistibly bring with it a new and happy spring for the nations." Well, they tried-- but who today plays that role-- perhaps only the Cubans come close, still inspiring Third World peoples and movements, but it is a great burden to place on the shoulders of a small nation. Is the world center of the Communist Movement today to be found in China, or is the role on hold? So what can we conclude about the Russian Revolution today? In this chapter Lenin thought the main feature of the revolution that would apply to other countries in the future was that it would be a model for revolutionaries to look to until more advanced economically developed capitalist countries had their own revolutions which would push the Russians into the background. He also thought that other countries would see their futures mirrored in the Russian Revolution. Let us hope he is wrong since what we see is that the Russians [and the Soviet people] fought and struggled for seventy years to build socialism and ended up with Putin. Nevertheless, the ideals of a communist future and a world free of human exploitation and war still motivate millions of people around the globe to struggle for a better world and in that sense Lenin and his revolution will continue to inspire working people and their allies until the final conflict (assuming that it has not already taken place). Next up is Chapter Two: “The Russian Revolution: An Essential Condition For Success” (2/10) AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed