|

There is no good reason to allow the evil empire to retain any legitimacy as the British royal family papers over the pillage it continues to benefit from. The death of Queen Elizabeth II, the longest-serving monarch of British royalty, has sparked global fascination and spawned thousands of clickbait reports of the details of her funeral. Americans, who centuries ago rejected monarchy, are seemingly obsessed with the ritualism, bizarrely mourning the demise of an elderly and fabulously wealthy woman who was born into privilege and who died of natural causes at the ripe old age of 96 across the ocean. Perhaps this is because popular and long-running TV shows about British royalty like “The Crown” have convinced us that we know intimate details about the royals—and worse, they cause us to believe we should care about a family that is a symbolic marker of past imperial grandeur. But for those who are descended from the subjects of British imperialist conquest, the queen, her ancestors, and her descendants represent the ultimate evil empire. India, my home country, celebrated its 75th anniversary of independence from British rule this year. Both my parents were born before independence, into a nation still ruled by the British. I heard many tales while growing up of my grandfather’s absences from home as he went “underground,” wanted for seditious activity against the British. After independence in 1947, he was honored for being a “freedom fighter” against the monarchy. Despite the popularity and critical acclaim of “The Crown” and movies and shows like it, I found a far stronger connection to the new superhero series “Ms. Marvel,” if for no other reason than the fact that it tackles the horrors of partition, a little-known (in the U.S.) legacy of the evil empire. As Pakistani writer Minna Jaffery-Lindemulder explains in New Lines, “The British changed the borders of India and Pakistan at the eleventh hour in 1947 before declaring both nations independent, leaving the former subjects of the crown confused about where they needed to migrate to ensure their safety.” As a result, 15 million people felt forced to move from one part of the South Asian subcontinent to another, a mass cross-exodus with an estimated death toll ranging from half a million to 2 million. Today, those contested borders, callously and recklessly drawn in 1947 by British officials acting at the behest of the crown, remain a source of simmering tensions between India and Pakistan that occasionally erupt into full-blown wars. This is the legacy of British monarchy. The United Kingdom enjoys a hideous distinction in the Guinness Book of World Records, for “most countries [62] to have gained independence from the same country.” One could argue that Elizabeth, who was gifted the throne and its title in 1952, did not lead an aggressive empire of conquest and instead presided over an institution that, under her rule, became largely symbolic and ceremonial in nature. And indeed, many do just that, referring to her, for example, as an “exemplar of moral decency.” Rahul Mahajan, author of Full Spectrum Dominance and The New Crusade, has a different opinion, referring in an interview to Elizabeth as a “morally unremarkable person with a job that involved doing extremely unremarkable things.” Mahajan explains further, saying that this was “a highly privileged person, given an opportunity to influence world events in some degree, which she had to do nothing to earn, who never did anything particularly remarkable, innovative, or insightful.” While Elizabeth’s 70 years on the throne were mostly spent overseeing an ostensible unraveling of British Empire in a world less tolerant of occupation, enslavement, and imperial plunder, just a few months into her role as queen, the British violently put down the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya. According to a New York Times story about how citizens in African nations today have little sympathy for the dead monarch, the squashing of the rebellion “led to the establishment of a vast system of detention camps and the torture, rape, castration and killing of tens of thousands of people.” Even if Elizabeth was not responsible for directing the horrors, they were carried out in her name. Over the seven decades that she wielded symbolic power, she never once apologized for what was done during her rule in Kenya—or indeed what was done in her family’s name in dozens of other nations in the Global South. It’s no wonder that Black and Brown people the world over have openly expressed disgust at the collective fawning of such an ugly legacy. Professor Uju Anya of Carnegie Mellon University, who is Nigerian, is under fire for her frank dismissal of Elizabeth after posting on Twitter that she “heard the chief monarch of a thieving and raping genocidal empire is finally dying. May her pain be excruciating.” Kehinde Andrews, a Black studies professor at Birmingham City University, wrote on Politico that he cannot relate to his fellow Britons’ desire to mourn Elizabeth, a woman he considered to be “the number one symbol of white supremacy” and a “manifestation of the institutional racism that we have to encounter on a daily basis.” Elizabeth may have appeared a benign, smiling elder who maintained the propriety expected from a royal leader. But she worked hard to preserve an institution that should have long ago died out. She was handed the throne after her uncle, the duke of Windsor, abdicated in order to marry a twice-divorced American. Both the marriage to a divorcee and the fact that the couple turned out to be Nazi sympathizers marked a low point for the royals. “The monarchy was in a really good position to fade away with this kind of clowning around,” says Mahajan. But it was Elizabeth who “rescued the popularity of the monarchy.” Further, Elizabeth quietly preserved the ill-gotten family fortune that she and her descendants benefitted from in a postcolonial world. “One thing she could, and of course should, have done and said something about is the massive royal estate,” says Mahajan. Observers can only estimate the royal family’s worth (Forbes puts the figure at $28 billion), assets that include stolen jewels from former colonies, pricey art investments, and real estate holdings across Britain. Britain’s new king, Charles III, now inherits the fruits of the evil empire. According to Mahajan, Charles “is apparently very bent on taking his fortune and investing it in such a way as to make himself as rich as possible.” According to the New York Times, “As prince, Charles used tax breaks, offshore accounts and canny real estate investments to turn a sleepy estate into a billion-dollar business.” The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in 2017 found that both Elizabeth and Charles were named in the leaked “Paradise Papers,” indicating that they hid their money in havens to avoid paying taxes. Fleecing taxpayers and living off stolen wealth—monarchy’s original modus operandi appears to be central to Elizabeth’s legacy, one she passes on to her son (who also won’t pay an inheritance tax on the wealth she left him). The British monarchy, according to Mahajan, “mostly represents a real concession to the idea that some people are just born better and more important than you, and you should look to them.” Mahajan adds, “It’s a good time for the popularity of this institution to fade away.” AuthorSonali Kolhatkar is the founder, host and executive producer of “Rising Up With Sonali,” a television and radio show that airs on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. She is a writing fellow for the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute. This article was produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute. Archives September 2022

0 Comments

9/18/2022 September 18, 2022-Marx’s writings on Asia: A sober assessment By: Ken Hammond & Liberation SchoolRead Now"A reverse-glass export painting of the Thirteen Factories in Guangzhou." By: Unknown Chinese artist. Source: Wikimedia. " This article was originally published on Liberation School on September 15, 2022." IntroductionThroughout most of recorded history, Asia has been the wealthiest region in the world. The riches of Asia attracted people from around the Old World, as exemplified by the travels of figures like the Venetian Marco Polo or the North African Ibn Battuta, who ventured to Asia in the 13th and 14th centuries and brought word of the lands and peoples he encountered, information which helped spark the age of Western exploration that began to establish ongoing interactions between Europe, India, China, and other parts of the continent. The rise of European capitalism drove the creation of commercial exchanges with Asia, as Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, and English traders built up networks of trade. With the Industrial Revolution the European powers, first the British and then others, were able to exert direct military power over Asian countries, and launched a period of imperialist domination which would persist until they were driven out in the middle years of the 20th century. The extraction of wealth from Asia created, for a while, a global economy in which the West held the levers of power based on the exploitation of labor both in the factories of the metropole and in the workshops, commercial farms, and plantations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In the course of the 19th century, a radical critique of capitalism emerged, primarily in the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, which was further elaborated and extended in analyses of imperialism by revolutionaries like V.I. Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg. These efforts were naturally focused first and foremost on Europe and its colonial extensions. This was the battleground on which the developing class struggle was taking its course. The dynamics of capitalist production, the imperatives of accumulation, and the social and cultural effects of exploitation and oppression were the critical arenas of the investigation and interpretation of the contemporary world. The analysis of the organization and functioning of capitalism, as well as its historical origins and development, remain the dynamic core of Marxist political economy. From the broad overview presented in the Communist Manifesto of 1848 through the exploration and elaboration of ideas and arguments in the notebooks he kept, including the Grundrisse from 1857-58 and the drafts of 1864-65, the Preface and Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy in 1859, and his published magnum opus, Capital in three volumes (the second and third edited by Engels posthumously), Marx produced a careful and precise explanation and understanding of the capitalist system. He was clear that his subject was primarily capitalism as it had developed in Britain, but with relevance to the geographically adjacent economies of France or Germany, and the historically antecedent formations of northern Italy and the Netherlands. The “Asiatic mode of production”Marx was also interested in and concerned with questions of the economic history of the rest of the world, both in terms of how European capitalism was reshaping global relations in his own time, and in how non-European societies had developed economically. He never produced a comprehensive exposition of his views on these topics, but there are scattered comments throughout his economic writings. One area about which Marx made numerous observations was Asia. Some of these gave rise to later debates and discussions about what has been called the Asiatic Mode of Production [1]. This, in turn, became part of the elaboration of a theory of the sequential development of modes of production, though in the official orthodoxy of the Soviet Communist Party in the 1930s, the Asiatic mode itself was no longer invoked, with the sequence rather beginning with a stage of primitive communal ownership (and it’s worth noting that “primitive” was not a value judgment but a descriptive category) [2]. The question of “Asia” is more than a matter of historical-materialist theory. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, and with the failure of revolutionary uprisings in Hungary and Germany after the end of World War I, the Communist International (The “Comintern” or the “Third International”) became a vital force for supporting and coordinating communist movements around the world. The question of revolution in the colonial world, in countries that were not part of the industrialized capitalist core of Western Europe and North America, became central to the work of the International. Some of the most dynamic movements emerged in places like China, the Dutch East Indies, French Indochina, and British India. There were intense debates about how these revolutions should be organized, about the nature of the political struggle in these societies, about what class forces were involved [3]. Marx’s ideas about “Asia” were important in these discussions, as Marxists tried to assimilate the social economies of Asian countries into their understanding of the development of capitalism and its place in the contemporary world dominated by Western imperialism [4]. These debates were also embroiled in the internal struggles for leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, with Stalin and Trotsky sharply disagreeing. In the end, of course, Stalin consolidated his position as the dominant figure in the Soviet system, and his view of the five-stage sequence of the historical development of modes of production became the only acceptable theoretical position by the late 1930s, as noted above. The influence of this model has remained significant in Marxist historical thought ever since. As scholars like Harry Harootunian have noted, a model like this was not intended by Marx to be a rigid, empirical description of a system, but more of a methodological device for abstracting an understanding of historical and economic dynamics [5]. In other words, the Asiatic Mode of Production was not an anthropological claim but rather a theoretical tool that allowed Marx to distinguish the particularities of capitalism from other social formations and modes of production. All of this leaves open the question of what Marx actually thought about Asia and how Asian societies related to the historical development of modes of production and the eventual emergence of capitalism in Europe. The idea that capitalism is a uniquely European development, that the rest of the world remained in some “pre-capitalist” stage and would only be incorporated into capitalism through direct encounters with European, or later American, capitalist imperialism, has shaped both Marxist and bourgeois understandings of history. Whether this is an accurate assessment of global economic history is perhaps not so simple a question to resolve. Recent scholarship on questions of “early modernity” have suggested that there were many aspects of economic and cultural life in Asian countries that were quite similar to features normally associated with the rise of capitalism in Europe [6]. Other studies have raised questions about the degree to which commercial capitalism may have developed in some non-European economies, and about Marx’s own views of the nature of some non-European societies [7]. Scholars in the “post-colonial” tradition, for example, often misread or selectively read Marx’s comments while neglecting to read his writings on colonialism and non-European social formations to portray him as Eurocentric or an advocate of colonialism [8]. It is in this context that I want to explore Marx’s economic writings to see how he portrayed and understood Asia— particularly India and China—and to raise the question of how Marxists today might apply Marx’s historical-materialist methodology to the analysis of the historical political economies of Asia as we have come to know them through more recent studies, with a breadth and depth of knowledge not available to Marx in the middle years of the 19th century. I will argue that, while Marx’s understanding of Asia was certainly flawed—especially in light of more recent evidence—this was the result of the information with which he was able to work. However, Marx’s method of historical-materialist inquiry provides the path to a very different understanding of the economic history of China that has been prevalent in both Marxist and bourgeois scholarship. “Asia”Before considering Marx’s statements regarding Asia, it will be useful to consider what the term means. The name originates in European antiquity and was used by the Greeks to refer to everything to their east, often with overtones of barbarism and otherness. Asia, though only vaguely understood, remained a realm of great interest to Europeans through the Middle Ages, with a trickle of commerce linking the West to the wealth of China or India via trans-Eurasian trade routes, both overland and maritime. By the early modern period, there was a heightened engagement with Asia as first the Portuguese and Spanish, and later the Dutch and English launched their voyages in search of access to the riches brought to their attention by Marco Polo and others [9]. In modern geography, Asia refers to a huge space encompassing the territory from the Ural Mountains in Russia, the Caspian Sea, and the Anatolian Peninsula across to the Pacific Ocean and extending down through the Malay Peninsula and across the Indonesian and Philippine archipelagoes. It includes countries ranging from Russia to Turkey, Iran and India to Pakistan, China, and the Central Asian states, Korea to Japan, the countries of mainland Southeast Asia to Indonesia, and others. Nearly 5 billion people live in what is called Asia, with a hugely complex range of variation in languages and cultures, and, of course, in economic conditions. In many ways, it designates a space that is not Europe, an otherness beyond the Eurocentric core. Marx’s deeper inquiry into Asia can be traced to his earliest economic writings, by which I especially mean his notebooks of 1857-58, known as the Grundrisse, the economic notebooks of 1864-65 (recently published in English for the first time), the three volumes of Capital (the third of which was edited by Engels from the material in the 1864-65 notebooks), and some additional comments in texts including the 1848 Communist Manifesto and the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy from 1859. These works include two basic kinds of comments about Asia. Some of these refer to Asia generically, while others refer more specifically to India and/or China. One kind of comment refers to developments taking place in the contemporary world, in the ongoing dynamic of the relationship between Europe and Asia which was unfolding in Marx’s own times. The other type, which are the main focus of my consideration here, are descriptions or characterizations of the political and economic features of Asia throughout history, a delineation of a social economic order which was outside the narrative of capitalist development Marx articulated for Europe. Marx was, of course, a creature of his own time, operating within a particular knowledge economy, an intellectual environment with specific contents and limitations. He was literate in several languages, both modern and classical, but not in any Asian language. The serious study of Asian history was in its infancy in Europe in the mid-19th century. More was known about India because of the activities of the East India Company and its merchants and administrators up to 1857, and a good deal of information about China had been accumulated from the two centuries of reports sent back by Jesuit missionaries and others (although these were strongly shaped by the specific contexts in which they were produced). But the bulk of information about Asia to which Marx had ready access was concerned with trade and with the challenges of colonial administration and control. Merchants, military leaders, and colonial or diplomatic officials, while perhaps personally intrigued by the customs or cultures of the lands they were exploiting, for the most part, did not devote themselves to acquiring the linguistic or historical knowledge which would have deepened their understanding of Asia’s long and complex past. Marx’s statements on Asia Perhaps the most famous of Marx’s pronouncements about an Asian topic came early, in the Communist Manifesto, which he published along with Friedrich Engels in 1848. In a long discussion of the rise of the bourgeois economic system and its spread around the world Marx wrote, “The cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate” [10]. This passage, while not a serious analysis of the functions of the capitalist system, nonetheless invokes some key concepts which recur throughout Marx’s observations about Asia. The use of the image of the “Chinese wall” which must be broken down, and the characterization of a “barbarian” other, highlight the idea that Asia is a place apart from, and different from, Europe, the birthplace of the bourgeois order. It’s important to note, however, that Marx used “civilization” in a derisive manner and never equated it with “progress” or “advancement.” Just after writing about how capital would break down the “Chinese walls,” for example, Marx and Engels state that capitalism forces “all nations, on the pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst” [11]. These basic motifs are elaborated in more substantive ways in Marx’s specifically economic writings, to which we will now turn. I will present these in chronological order from the succession of texts in which they appear, and then draw some overall conclusions about the essential features of Marx’s view of Asia and its political-economic history. After the tumultuous years of revolutionary activity in the late 1840s and the trauma of the post-revolutionary retreat of communist activities across Europe, Marx moved to London, where he would live for the rest of his life. The first half of the 1850s was a difficult period, during which Marx struggled to maintain his family and to work with many of the other continental political refugees that wound up in Britain. But by the second half of the decade, he was able to settle into the period of deep study of political economy which would culminate in the writing of Capital. He spent long hours in the Reading Room of the British Library and in his makeshift study at home. He took copious notes on a wide range of primary and secondary sources, keeping massive notebooks and drafting and re-working versions of what would become the three volumes of his masterwork, Capital. Some of Marx’s writings reached published form in his lifetime or shortly thereafter, as with the final two volumes of Capital. Others, especially the notebooks he kept in the late 1850s and early-to-mid 1860s, were long neglected and not published until the mid-20th or early 21st centuries. The first set of notebooks, published under the title Grundrisse (ground plan/outline/rough sketch), were compiled in 1857-58, although only the “Introduction” was released and translated before 1939. The Grundrisse contains numerous comments on trade with India or China, including information about exchange rates for silver and gold and other materials dealing with the contemporary development of relations between Europe and Asia. These are beyond the scope of this study, which is concerned with Marx’s understanding of the historical nature of Asian economies. Much of this material is presented in Kevin Anderson’s Marx at the Margins, where he also engages with Marx’s journalistic writings about China, India, and other Asian questions [12]. In these notebooks, Marx makes several comments on what he calls the “Asiatic form” of economic society, as well as other observations about Asia or the Orient. Many of these are found in the section on “Forms which precede capitalist production” at the end of Notebook IV and in Notebook V. In a section on property Marx writes: Amidst Oriental despotism and the propertylessness which seems legally to exist there, this clan or communal property exists in fact as the foundation, created mostly by a combination of manufactures and agriculture within the small commune, which thus becomes altogether self-sustaining, and contains all the conditions of reproduction and surplus production within itself [13]. Shortly after this, while reflecting on the nature of cities in pre-capitalist societies, he comments that “Asiatic history is a kind of indifferent unity of town and countryside (the really large cities must be regarded here merely as royal camps, as works of artifice erected over the economic construction proper)” [14]. This is followed over the next few pages by two statements on the “Asiatic form:” In the Asiatic form (at least, predominantly) the individual has no property, but only possession; the real proprietor, proper, is the commune—hence property only as communal property in land… The Asiatic form necessarily hangs on most tenaciously and for the longest time. This is due to its presupposition that the individual does not become independent vis-à-vis the commune; that there is a self-sustaining circle of production; unity of agriculture and manufactures, etc. [15]. Marx adds a further reference to common property in India, writing that “common property in the older, simpler form, such as is found in India and among the Slavs” [16]. He continues this discussion and looks forward to the development of subsequent modes of production in the slave and feudal forms, while noting that the Asiatic form is particularly resistant to historical change: Slavery and serfdom as thus only further developments in the form of property resting on the clan system. They necessarily modify all of the latter’s forms. They can do this least of all in the Asiatic form. In the self-sustaining unity of manufacture and agriculture, on which this form rests, conquest [of neighboring territories] is not so necessary a condition as where landed property, agriculture, are exclusively predominant [17]. Marx elaborates that in these new modes of production the individual loses the organic integration in a community which gave them the dual status of being a member of the group and a proprietor of a share of the communal resources: In the oriental form this loss is hardly possible, except by means of altogether external influences, since the individual member of the commune never enters into the relation of freedom towards it in which he could lose his (objective, economic) bond with it…Slavery, bondage etc., where the worker himself appears among the natural conditions of production for a third individual or community (this is not the case e.g. with the general slavery of the orient, only from the European point of view) [18]. In summarizing his thoughts on pre-capitalist forms, he returns to his basic characterization of historical Asiatic or oriental social economies, where “the original form of this property is therefore itself direct common property (oriental form)” [19]. The Grundrisse includes one additional comment which relates the general nature of the Asiatic form to a supposed specific practical feature, particularly, but not solely, associated with India: “In the original, self-sustaining communes of Asia, on one side no need for roads; on the other side the lack of them locks them into their closed-off isolation and thus forms an essential moment of their survival without alteration (as in India)” [20]. Two years after his compilation of the Grundrisse, Marx wrote a preface A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, a project which included a modified form of the first three chapters of Capital. In the preface, he outlined a sequence of the historical development of modes of production. “In broad outline,” as he writes, “the Asian, ancient, feudal, and modern bourgeois modes of production may be designated as progressive epochs of the socio-economic order [21]. This concept of a step-by-step succession of forms, with the Asian form as the starting point, is not developed further here, but it gave rise to a tradition of thought among certain later writers, such as Karl Kautsky, of taking this sequence as a universal template that could be applied to any given society around the world. Yet it’s important to note that Marx’s presentation here is didactic and schematic in nature and can’t be isolated to imply that Marx held a “stageist” approach to history. Early in the mid-1840s, Marx wrote that “to hold that every nation goes through this development internally would be as absurd as the idea of that every nation is bound to go through the political development of France” [22]. Nonetheless, Kautsky’s interpretation dominated many Marxist debates in the early-mid 20th century. The specification of the Asian form gave way to the invocation of a “primitive” or “primitive communal” form in later versions. This was ultimately enshrined, with effects which will concern us further, in Stalin’s proclamation of the stages of historical development set out in his essay “Dialectical and Historical Materialism” and in the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Short Course). Thus, it’s worth restating that Marx was presenting a didactic model that was necessarily rough and schematic, rather than articulating a fully fleshed-out theory of development. Marx made several further statements of his ideas about historical Asian economies and societies in the notebooks which he kept in 1864-1865—which were the basis of the second and third volumes of Capital as edited by Engels—and in the first volume, which was the only one published (and republished) by Marx starting in 1867. In the 1864-1865 notebooks, Marx returns to the topic of property: The legal conception [of landed private property] itself means nothing more than that the landowner can behave in relation to the land just as any commodity owner can with his commodities; and this idea—the legal notion of free private landed property—arises in the ancient world only at the time of the dissolution of the organic bonds of society, and in the modern world only with the development of the capitalist mode of production. In Asia it has simply been imported here and there by Europeans. He also gives a basic description of the organization of production in Asian economies, specifically referring to India in one instance, and to Asia more broadly in another, and invoking the idea of a “natural economy:” The existence of domestic handicrafts and manufacture as an ancillary pursuit to agriculture, which is the basic activity, is the condition for the mode of production on which this natural economy rests, both in European antiquity and medieval times… The first volume of Capital, which is devoted to the analysis of the capitalist mode of production using England as a “chief ground” to elaborate an abstract model of capitalist production in general, includes a number of comments on trade with India, China, or Asia more broadly. Neither Marx nor Engels considered England to be a “closed national economy” and, from the 1840s onwards, analyzed England as a colonial power. Yet in Capital Marx has little to say about what he thought of as “pre-capitalist” economics, save for one important characterization of the nature of political economy in Asian history: The simplicity of the productive organism in these self-sufficing communities which constantly reproduce themselves in the same form and, when accidentally destroyed, spring up again on the same spot and with the same name—this simplicity supplies the key to the riddle of the unchangeability of Asiatic societies, which is in such striking contrast with the constant dissolution and refounding of Asiatic states, and their never-ceasing changes of dynasty. The structure of the fundamental economic elements of society remains untouched by the storms which blow up in the cloudy regions of politics [25]. These passages yield a number of defining features that Marx felt characterized Asian societies and economies over the long sweep of history [26]. These can be summarized as follows:

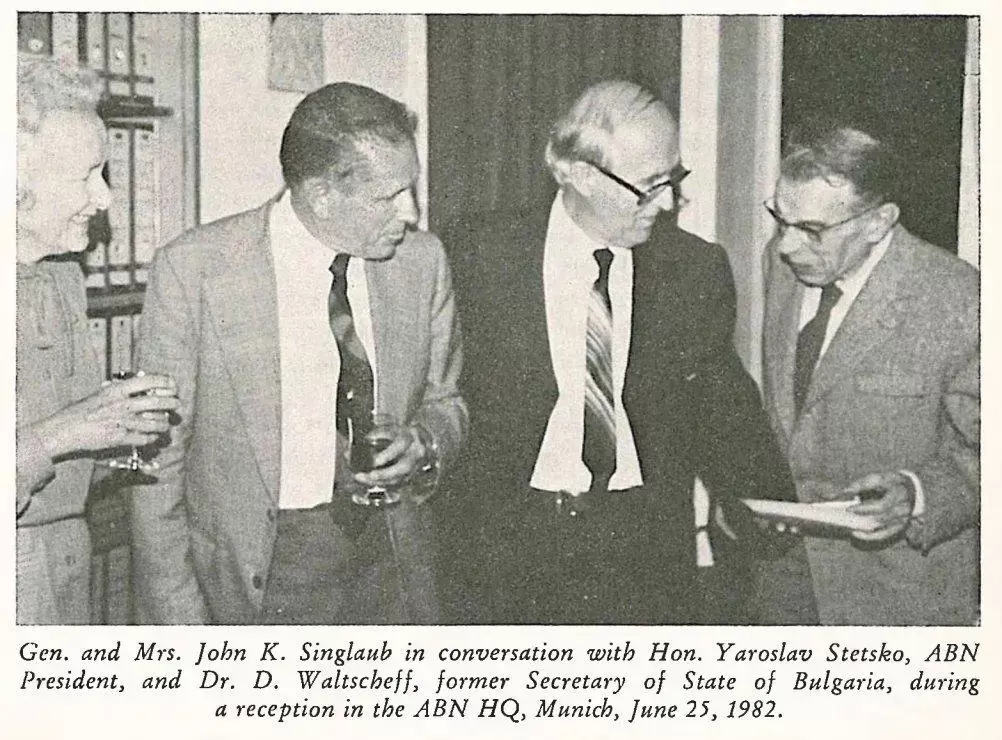

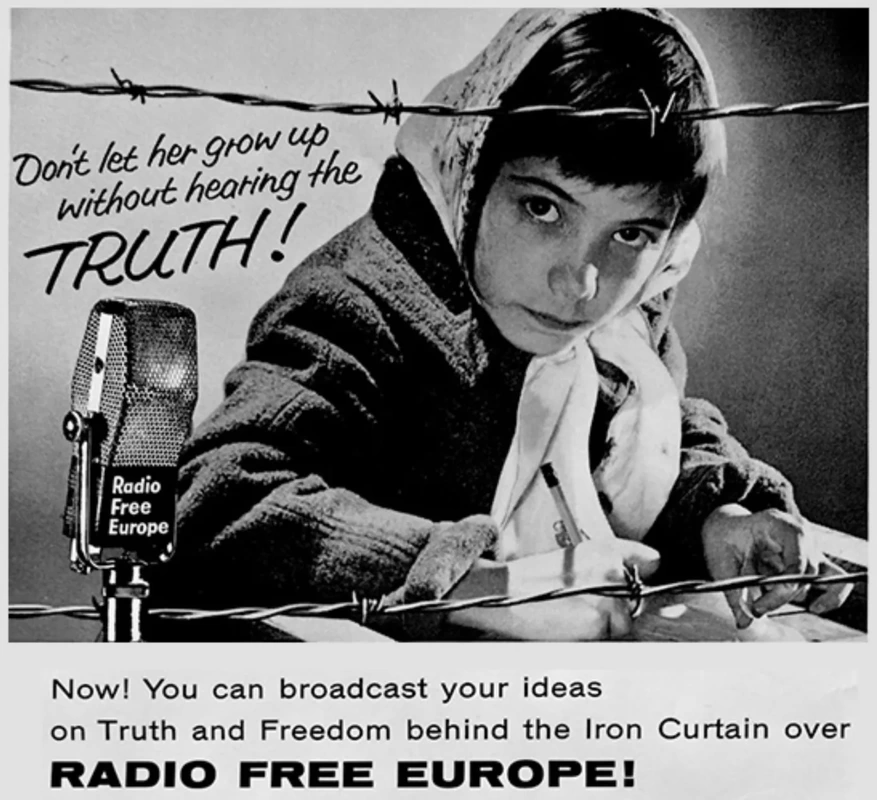

This model of an Asian form of political economy, with the geographic extent of its applicability left ill-defined but expansive, along with the concept of history as a set succession of modes of production in a sequence that was universal for human societies around the planet, became fixed in some later forms Marxist thought. As noted above, the German Social Democratic leader Karl Kautsky wrote about China and Asia in 1886 using exactly this model of an “Asiatic” form of political economy and of the successive stages of social development [27]. Indeed, these same concepts featured in non-Marxist portrayals of Asia as autarkic and unchanging by such influential thinkers as Max Weber as well [28]. Asia and Chinese Marxism in the 21st centuryNot all Marxist students of Chinese history accepted these defining features. In 1926-1927, the Bolshevik Karl Radek, at that time the Director of the Sun Yat-sen University for the Toilers of China in Moscow, gave a series of lectures on China in which he challenged both the characterization of China as static and unchanging and the effort to assimilate Chinese history to the European-derived model of successive stages. Working with recent scholarship on China that had not been available to Marx, Radek rejected the idea that China remained in a feudal stage until the arrival of European imperialism in the 19th century, and argued instead for an understanding of China’s historical political economy which was dynamic and featured elements of mercantile capital and highly commercialized agricultural production [29]. Radek’s views, however, did not become widely accepted among Marxists in the Soviet Union or beyond. Radek was embroiled in the political controversies within the Soviet leadership, being closely associated with Trotsky, in opposition to the rising power of Stalin in the later 1920s [30]. As Stalin consolidated his dominance and Trotsky went into exile, Radek was largely silenced and came to conform to the orthodox version of historical materialism, including the view of successive stages of development applicable to all societies. Given the leading, guiding role of the Soviet Union in the world Marxist movement through the middle of the 20th century, Stalin’s version of a universal template of historical development through successive modes of production, and the characterization of Asia, especially China, as a static, feudal, pre-capitalist system, came to be accepted by Marxist scholars in both the socialist states and in the capitalist world. The question remains, then, how well this representation fits the actual history of Asian, especially Chinese, political economies. Modern studies of Chinese economic history especially have yielded radically different understandings, beginning with Naitō Torajiro’s work on the commercial revolution of the Tang-Song period in the 1920s through recent works like William Liu’s study of the Chinese market economy from 1500-1800, or Richard von Glahn’s comprehensive economic history of China. Even these works, however, refrain from referring to China’s historical economy as capitalist, let alone applying that definition to Asia more broadly. Scholars such as Kenneth Pomeranz and Prasannan Parthasarathi, cited above, have argued that the economies of China and India in fact were equivalent to those of Western Europe on the threshold of the Industrial Revolution in many important ways. It is beyond the scope of this essay to set out a full investigation of how China’s economy, especially over the last millennium of imperial history, may have accorded with Marx’s own descriptions of the essential features of capitalist production. Further work must be done on this matter. ConclusionFor the moment, I want to simply conclude with a reminder and a suggestion. The reminder is that throughout Marx’s development, he moved beyond associating the “Asiatic Mode of Production” with “oriental despotism” precisely because he “was very concerned about the question of sources, and criticised the poverty of the empirical data on which British writers based their arguments, which were often dictated by colonial interests” [31]. The suggestion is that a critical task for Marxists is to apply the historical-materialist methodology embodied in Capital and other texts of political economy to the understanding of Asia and China in order to reach a new appreciation of the complex global history of capital and the rich diversity of economic forms and developmental trajectories that preceded, accompanied, and followed the transformative expansion of European and American imperialism and the consolidation, for a brief period, of a Western-dominated global capitalist system. Contemporary struggles against imperialism and for building a socialist future will be strengthened by a more accurate understanding of the dynamics of Asian history and its implications for the path ahead. Marxist historical materialism has played a central role in the Chinese revolution since its introduction there in the early twentieth century. Chinese scholars and activists, perhaps most prominently Mao Zedong, have used this creatively and adapted Marxist theory to the concrete material realities of China. Applying this methodology to China’s historical political economy extends and deepens this work, and will provide not only a greater understanding of the past, but also insights into the contemporary development of socialism in China. References [1] Timothy Brook, The Asiatic Mode of Production in China (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1989). [2] Central Committee of the CPSU, History of CPSU (Short Course) (New York: International Publishers, 1939); and Joseph Stalin, Dialectical and Historical Materialism and Other Writings (New York: International Publishers, 2020). [3] E.H.Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution (Vol. 3) (London: Pelican Books, 1966). [4] V.I. Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1976). [5] Harry Harootunian, Marx After Marx: History and Time in the Expansion of Capitalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017). [6] See the “Early Modernities” special issue of Daedalus 127, no. 3 (1998); Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021); Prasannan Parthasarathi, Why Europe Became Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600-1850 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Ken Hammond, “Beyond the Sprouts of Capitalism: China’s Early Capitalist Development and Contemporary Socialist Project,” Liberation School, 13 September 2021. Available here. [7] Jairus Bannajee, A Brief History of Commercial Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020); and Kevin B. Anderson, Marx at the Margins: on Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010). [8] Lucia Pradella, “Marx and the Global South: Connecting History and Value Theory,” Sociology 51, no. 1 (2017): 147. [9] An overview of the historical awareness and understanding of Asia by Europeans down to the 18th century is found in Jürgen Osterhammel, Unfabling the East: The Enlightenment’s Encounter with Asia (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018). More critical analyses of the construction of European conceptions of Asia by the beginning of the 19th century and down to Marx’s time are in Geoffrey C. Gunn, First Globalization: The Eurasian Exchange, 1500-1800 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003); and Andre Gunder Frank, ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 8-34. [10] Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto (New York: International Publishers, 1948/2021), 13. [11] Ibid. [12] Anderson, Marx at the Margins. [13] Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of a Critique of Political Economy, trans. M. Nicolaus (London: Penguin Books, 1939/1973), 473. [14] Ibid., 484. [15] Ibid., 484, 486. [16] Ibid., 490. [17] Ibid., 493. [18] Ibid., 494, 495-496. [19] Ibid., 497. [20] Ibid., 525. [21] Karl Marx, Preface and Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1959/1976), 4. [22] Karl Marx, “Draft of an Article of Friedrich List’s book Das Nationale System der Politischen: Draft of an Article on Friedrich List’s Book Das Nationale Oekonomie,” in Marx-Engels Collected Works (Vol. 4) (New York: International Publishers, 1975), 281. [23] Karl Marx, Marx’s Economic Manuscript of 1864-1865, trans. B. Fowkes and ed. F. Moseley (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), 715, 778. [24] Ibid., 774, 782. [25] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. B. Fowkes (London: Penguin Books, 1867/1976), 479. [26] In his introduction to the edited volume The Asiatic Mode of Production in China, Timothy Brook sets out a set of such characteristics as defined by scholars in the People’s Republic in the 1970s and ‘80s. These are similar to those in this essay, but include a focus on the hydraulic thesis of oriental despotism, which is absent from the texts considered here. [27] Karl Kautsky, “Die Chinesischen Eisenbahnen und das Europäische Proletariat,” Die Neue Zeit 4 (1886): 515-549. [28] Max Weber, The Religion of China (New York: Free Press, 1968). [29] Alexander V. Pantsov, ed., Karl Radek on China: Documents from the Former Secret Soviet Archives (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020), 22-78, 208-225. [30] These controversies and policy disputes, especially as related to China, are delineated in fine detail in Carr,The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917-1923 (Vol. 3), 484-540; and Carr, Socialism in One Country, 1924-1926, (Vol. 3) (London: Pelican Books, 1972), 693-830. [31] Lucia Pradella, “Beijing between Smith and Marx,” Historical Materialism 18, no. 1 (2010): 94. AuthorArchives September 2022 Under any social structure of accumulation, there exists a Master Signifier, which serves as the structuring principle of discursive operations. These historically contingent operations operate at two levels: the ontic and the ontological. The ontic refers to the ideological delimitation of what can be talked about, establishing the contours for the struggle of hegemony within a specific accumulation regime. Hence, it is the domain of politics, of Reality. As Alicia Valdes notes, “[t]he ontic level of politics establishes which elements, issues, demands, or interests are worth entering politics. It is the level concerned with beings, their needs, and desires. The ontic level of politics is responsible for limiting the signifying chain of political discourses”. The ontological refers to the inclusion and exclusion of people that a discourse orchestrates, setting limits to who can speak in the discourse, and intervene in politics and Reality. This can be clarified through the distinction between subjection and subjectification. While the former denotes the way in which each individuals’ interaction with society is necessarily mediated through a discourse, the latter denotes a form of discursive emplacement through which the individual comes to completely identify with the signifying chain. As such, the ontological pertains to the Real, the Political. In the words of Valdes: “The ontological level of politics establishes who can intervene in politics…At the ontological level…a framing operation establishes limits between the space for existence and the space for ex-sistence. Those who produce and reproduce the signifying chain of political discourse inhabit the place for existence…The place of ex-sistence is where the Real, as the Political, inhabits. In other words, the ontological level of politics sets limits to the being of beings that accede to the ontic.” The status of the ontological as the machine that excludes certain people means that it is home to the explosiveness of the Political, the element that can leap out of the zone of non-being to disrupt the very division of the ontic and the ontological. The dualities of ontic and ontological, Reality and Real, politics and Political, subjection and subjectification, existence and ex-sistence, emerge from the constitutive lack at the heart of human subjectivity. The emergence of the signifying order directly coincides the formation of a constitutive lack at the heart of human subjectivity. In the language system developed by humans, significatory connotation confers an additional or excess meaning on objects that is not reducible to their empirical existence. This translates into the construction of a division between the signifier and signified, between the name and the idea of the object, with no amount of linguistic effort ever being able to close this gap. We keep moving from one signifier to another along the signifying chain, as one signifier constantly refers to another in a perpetual deferral of meaning. This separation of the signifier and the signified – labeled “symbolic castration” – also denotes the separation of the subject from the satisfying object (“objet a”). All of the subject’s diverse activities within the system of signification come to revolve around the attempt to rediscover this object that it never possessed. Since absence animates the subject, repetitious attachment to failure – attributable to the loss of the object that signification entails – becomes a defining characteristic of human subjectivity. We unconsciously satisfy ourselves and gain enjoyment/jouissance through successive efforts to attain a missing satisfaction. In the arrangement created by a Master Signifier, the aforementioned dualities serve as the Symbolic framework – the network of language and order, norms, customs, habits, rules, laws, etc. – through which our constitutive lack can be dealt with. The mechanisms of the Symbolic allow for the subjectification of certain groups through a form of political identification that enables an affective attachment toward the objet a offered by a particular discourse. This affective attachment allows the subject to cope with symbolic castration by pushing it to locate its identity in the ideal images constructed by a hegemonic narrative. Once this process of identitarian location is completed, the subject successfully enters the signifying chain. However, as Valdes reminds, “success of symbolic identification does not imply the achievement of a complete identity, as the lack of the subject makes it an impossible campaign. Instead, it only assures the entrance in the continuous process of identification that can occur once the subject enters the Symbolic register. Success is the affective attachment that certain subjects can develop toward the ideal subject that emerges from a specific discursive operation.” Apart from the subjectified agents of the Master Signifier, there are those who fail to engage in symbolic identification. This failure is “the rejection certain subjects receive when attempting an identification, whether it is a result of their rejection of the Symbolic order or a result of their imposed incompatibility with the subject offered in the Symbolic register.” Taking into account the presence of these subjects, Valdes distinguishes between “subjects with existence” and “subjects with ex-sistence”. The former indicates subjects whose constitutive lack, and thus inability to form a full identity, is temporarily sutured through a successful symbolic identification with the objet a posited by the discursive engine of a Master Signifier. These subjects inhabit the space of Reality. The latter indicates subjects who, on top of the constitutive lack instituted by the language system, have a constituted lack. This second constituted lack “results from their resistance or prohibited entrance toward the ideal or the normativity that offers the Symbolic order. These subjects inhabit the Real.” The Master Signifier that represents capitalism is the commodity form. In the economic domain, capitalism works through the homogenizing logic of money and market, wherein the former equates commodities on the basis of abstract socially necessary labor and the latter equates individuals as interchangeable market actors. This market actor is empty in terms of identity because it is simply supposed to pursue its own self-interest. To fill this isolated particularity of the market actor, the capitalist Master Signifier discursively posits the promissory gesture of accumulation and commodities as the objet a. Through this discursive operation, the future is said to embody a type of satisfaction unavailable in the present and attached to one’s investment in the capitalist system. However, this objet a, this symbolic identification with the commodity form, is only fully available to the capitalists and not to the workers. In the words of Todd McGowan: “Capitalists themselves at least can fill the emptiness of their particularity with money and other commodities. Capitalists have their particular accumulation to give themselves a content. Even if this accumulation offers them nothing but dissatisfaction after dissatisfaction, they can at least hope that some future level of accumulation will provide what they’ve been missing. This hope is what keeps them invested in the capitalist system, despite its broken promises. Workers don’t have that option. In Marx’s account, they are pure form without content and thus the engine for revolutionary subjectivity…Without the possibility of the accumulation that gives the capitalist a content, the working class lacks the identity that the capitalist class has. Because its particularity is empty, it can assume the mantel of the revolution without sacrificing anything but its chains. The working class has everything to gain and nothing to lose with the turn toward revolution.” Pure form without content. This formulation, in addition to conveying the economic status of workers, can also be explained in a logical way through certain psychoanalytic tools. For this, we need to take a conceptual detour through the notion of the “hysteric”, which is defined as the subject that, being subjected to the Symbolic, is not accepted by the signifying chain of the Master Signifier, by the Other. The lack of acceptance leads to the rejection of the Other by the subject and the decision to embrace constitutive lack as the main principle of ex-sistence. In the discourse of the capitalist Master Signifier, bourgeois subjectivity believes that it has gained jouissance through commodities and accumulation. However, having this illusory commodified jouissance leaves one constantly threatened by the idea of its loss and incessantly striving for more authentic possession. The capitalist subject has established fantasmatic coherence within the Master Signifier of commodity, but this coherence remains fragile because bourgeois subjectivity constitutes itself in reference to the threat of castration. Thus, the problem with the commodity form, with the capitalist objet a, stems not simply from the constant threat of loss but also from the impossibility of ever really having it. Bourgeois subjectivity exists in relation to an ideal of perfect having, a non-castration that is structurally unattainable. In contrast, the proletarian hysteric, the subject of ex-sistence, does not depend upon the ideal of non-castration since its economic position seals it from the illusion of endless accumulation, turning it into the placeholder of the Real. Giving up on the dream of having commodities, the proletarian hysteric constitutes itself through not having the commodity, and symbolic castration therefore functions as the foundation of proletarian subjectivity. Proletarian subjectivity does not require the threat of symbolic castration because it embodies the threat itself, the constitutive lack. In other words, the proletarian hysteric derives jouissance from the complete embrace of the Real, adopting the standpoint of lack to fight against the illusion of commodified plenitude. Now, to return to the dialectic of form and content, the proletarian hysteric is pure form because, in the discursive universe of the capitalist Master Signifier, it is ontologically excluded and not supposed to speak; consequently, it is unintelligible to the Reality of bourgeois politics. Insofar that the proletarian Political is unintelligible to the ontic narrative of the commodity, its content can’t be prioritized. The mere fact of speaking by the proletarian hysteric dislocates the syntax of the capitalist Master Signifier and allows for the Real to make itself felt in the Symbolic. Thus, the proletarian Real – the pure negativity of capitalism that lingers as unassimilable into the Symbolic order and manifests itself within the periodic turbulences of the capitalist system – emerges at the limits of the capitalist Symbolic, when the Symbolic loses its transparency and clearly fails to disambiguate itself. The failure of disambiguation means that the commodity-as-objet a ceases to trouble subjectivity as a promised but necessarily impossible plenitude. This disruption of the capitalist Master Signifier is completed through the inscription of the Real within the Symbolic, which crafts a new Communist Master Signifier whose discursive operation is based upon the fundamentality of the non-traumatic signifier of the lack in the Other. This signifier of the lack in the Other functions in the following way. For bourgeois subjectivity, proletarian subjectivity is its Other, the hysteric who is defined by the lack of commodified jouissance. For proletarian subjectivity, however, there is no negative Other in relation to which it can construct its positive identity and fantasies regarding the objet a. Hence, the proletariat is a subject in which, to borrow Alenka Zupancic’s words, “[t]he nonexistence of the Other is itself inscribed into the Other.” Insofar that the proletariat is the “Other the inconsistency of which is inscribed in it,” the Communist Master Signifier comes to center around the signifier of the lack in Other. This allows for a politics which emphasizes the internally divided nature of the human subject, the aspect of the Real which is always concealed by capital’s uncritical fantasies of wholeness. The only way to fully come to terms with the constitutive lack that inheres in the being of humanity is to orient politics toward its conscious and controlled materializations in the form of democratically crafted fantasies. AuthorYanis Iqbal is an independent researcher and freelance writer based in Aligarh, India and can be contacted at yanisiqbal@gmail.com. His articles have been published in the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and several countries of Latin America. Archives September 2022 9/15/2022 Bill Gates Failed Effort to Feed Africa:Was he even trying to help in the first place? By: Edward Liger SmithRead NowHealthcare administration students in the United States have no choice but to learn about private vs public interests, and the power that private interests have in crafting the Nation’s healthcare policy. Essentials of Health Policy and Law is a fairly standard healthcare administration textbook that budding health policy experts are given to study in American universities. The text uses health policy decisions made in recent years by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as an example of the way private interests control public health policy. According to the book, the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation “provides grants to develop crops that are high in essential vitamins and minerals to improve the nutrition of people in developing countries” (Wilensky, 2023). A very uncritical examination of the way investors like Gates use their wealth to make important decisions that affect millions. The text is referring to the ‘Green Revolution’ initiative in Africa, which in the field of healthcare administration, is what’s considered a health policy decision. The initiative was launched by the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) , a philanthropic group led by Bill Gates and many other wealthy investors who have spent billions of dollars bringing fertilizer, seeds, and productive agricultural infrastructure to underdeveloped nations in Africa. An initiative which the investors promised would decrease poverty, malnutrition, and other metrics related to standard of living. However, a yearly progress report from the Gates Foundation itself has cast doubt on the effectiveness of the initiative, which critics argue is actually intended to maximize the profits of multinational agricultural companies selling commodities like seeds and fertilizer, rather than feed people in Africa. An African farming summit was recently held in Rwanda where many African farmers and activists criticized the Green Revolution and requested that philanthropists discontinue their support for the initiative. Critics from Africa and elsewhere across the globe came together to argue that the Green Revolution has had the opposite of its intended effects. African Agricultural experts claimed that chemicals in Western fertilizers have led to decreased fertility in the African soil. Simultaneously, small African farmers have continually gone into debt from buying these fertilizers and other agricultural materials from Western multinationals. Many at the summit also criticized how the initiative distributes funds, claiming that Green Revolution grants are not given to small African farmers for the purpose of developing infrastructure, but are diverted towards large companies who sell seeds and other agricultural products. When resources are given to farmers it is usually in the form of credit, meaning a bank loan that must be paid back with interest to Western banking institutions. Often giving farmers the money needed to purchase agricultural commodities from various multinationals, but leaving them trapped in a downward spiral of debt if they can’t pay back their loans. A system of resource allocation which has done much to increase the welfare of Western finance capital in Africa, but very little to increase the public welfare of African people. Gabriel Manyangadze of the Southern African Faith Communities suggested that the purpose of the Green Revolution was always to maximize the profits of wealthy philanthropists who never intended to decrease malnutrition. Manyangadze called for a new “Green Restoration” plan where grants are diverted towards small African farmers instead of large multinationals. The entire summit in Rwanda was summarized in a fantastic piece written by Nina Shapiro and published in The Seattle Times titled Gates Funded ‘green revolution’ in Africa has failed. Perhaps in response to the Rwanda summit or the recent piece from Shapiro, Bill Gates decided to do an interview with the New York Times on September 13th just a few days after Shapiro’s article was published. Gates was mildly critical of the Green Revolution but pointed to climate change and the war in Ukraine as reasons why the initiative failed to meet its goals. Gates says “The Green Revolution was one of the greatest things ever. But then we lost track… Helping farmers has got to be the very top of the climate adaptation agenda… credit for fertilizer, cheap fertilizer, better seeds that we should be very intent on- funding those things and setting ambitious goals.” (Wallace-Wells, 2022). Admitting that the initiative has failed to fulfill any of its promises, but ignoring the specific criticisms repeatedly voiced by African policy analysts. Gates instead argues the opposite of those at the Rwanda Summit, pushing for more fertilizer sales and more credit for African farmers. Doing little to dispel the idea that the Green Revolution has always been an initiative that weaponizes philanthropy for the purpose of maximizing profits on Wall Street. AGRA has made it clear that they are going to be ignoring the Rwanda summit and continuing to follow the strategy laid out by Gates in the New York Times. The organization recently announced they will be deepening their influence over African Health Policy with a new five-year initiative emphasizing environmentalism, launched with the help of $200 million from the Gates Foundation. Gates remains steadfast in his opinion that capitalistic market-based solutions are the key to improving African Agriculture, pointing to Kenya as a Green Revolution success story, which he attributes to a market-friendly economy that connects Kenya to larger global markets. Kenyan agricultural activists were present at the summit in Rwanda including Celestine Otieno who said of the Green Revolution “I think it’s the second phase of colonization.” Similarly, at a news conference organized for the purpose of publicly criticizing AGRA, Anne Maina, national coordinator of the Biodiversity and Biosafety Association of Kenya, asked “When will you stop pushing for these Green Revolution models that have failed?” The New York Times interview with Gates makes no mention of these criticisms from Kenyan activists, and offers no critical analysis of his claim that AGRA succeeded in Kenya. There is a striking contrast between the analysis of the Green Revolution given by Bill Gates and Western Healthcare Administration textbooks, vs the analysis given by health and agriculture policy experts in Africa. It serves as a prime example of the way private interests dominate global health policy decisions with little to no input from the masses of people who their decisions directly affect. Spokespeople for these private interests, such as Gates, often respond indignantly to any criticism of their philanthropic efforts, touting their initiatives as great successes, which can only be improved if we go further and do more! All the while deflecting blame to external factors like climate change in order to brush aside the failures of their initiatives. Private interests can then blast their messaging through a loudspeaker all across the country with the help of corporate friendly news outlets like the New York Times. Meanwhile events like the Summit of African leaders in Rwanda get very little coverage in the Western Press. Though Bill Gates had access to the giant media platform that is the New York Times, he failed to make a convincing argument for the continuation or AGRA, and in doing so he failed to make a good argument for capitalistic market-based solutions in general. When asked about the role of commodity speculation, which has led to price hikes in food products and supply chain disruptions, Gates responded “the market actually works amazingly well” before later admitting that African farmers are being “priced out of the market” for agricultural supplies. His solution to this of course is more credit for farmers, so they can purchase more productive commodities, sell more food, and hopefully pay those loans back before spiraling into a debt trap. The most interesting question posed to Gates by NYT interviewer David Wallace-Wells had to do with the poverty alleviation efforts in China. I wanted to ask you about poverty. It has gotten an enormous amount of attention over the past couple of decades, and the progress has been really remarkable. But quite a lot of it reflects progress in China, Right? How much do you think we should expect the long-term trend to continue, given that China has sort of finished eradicating real poverty and progress would have to come now from elsewhere? It’s rare these days to see anyone in Western media speaking highly of China, but it seems the country’s incredible poverty alleviation efforts can no longer be ignored. Gates himself admits that China has done a good job as part of his confused and jumbled answer. He goes on to say that there has also been some progress in other high population Asian countries, and he is optimistic that India will soon begin reducing poverty “in its own sort of up and down way.” However, Gates thinks poverty in Africa will be more difficult to address saying “we’re faced with the mind-blowing challenge of Africa, where population growth is still there.” It’s unclear what kind of connection Gates was trying to draw here between high population countries in Asia vs those in Africa, but his overall point seems to be that African countries will not be able to lift themselves out of poverty the same way China did, and one reason for this is that the African population is increasing. An argument reminiscent of the English economist Robert Thomas Malthus who argued that excess population growth created the Irish potato famine, rather than capitalism and colonialism (Berezow,2020). Similarly to Malthus, Gates never questions capitalism or the effectiveness of the Market, repeatedly saying it works very well, but with little evidence in support of his claim. The preeminence and supremacy of the capitalist market is always assumed. If Mr. Gates looked a little closer at China’s poverty alleviation efforts; he may have some second thoughts about the efficiency of private markets. Though it’s unlikely that he would ever admit this given the incredible amount of wealth that he has accumulated through market transactions. However, for those of us who don’t make millions of dollars through global commodity markets each year it may be useful to take a closer look at what China has done to eradicate poverty. An intensive study of China’s poverty alleviation programs from the Tricontinental Institute contains many interviews with experts in Chinese economics including Justin Lin Yifu, former chief economist of the World Bank who now works as a professor at Peking University in China. In contrast to the rest of the world, the Chinese government has played a crucial part. Poverty eradication would not have been achieved merely through the role of the market had the government not paid great attention to the issue of the poor people.” The researchers from Tricontinental go on to summarize Lin’s analysis saying, “In other words, a combination of the ‘visible’ and ‘invisible hand,’together with the mobilization of broad sectors of society, was the hallmark of China’s poverty alleviation.” (Tricontinental,2021). When the researchers refer to the ‘invisible hand’ they mean the natural effects of undisturbed private market exchange which was first conceptualized by Adam Smith. The ‘Visible Hand,’ on the other hand, refers to centralized economic plans organized by the Chinese people and Government intended to do what the market can’t. Party cadres are assigned to various areas to make sure people’s basic needs are being met, social welfare programs and safety nets have been set up, largely funded by publicly owned companies like Baowu steel, one of the largest steel companies in the world. This is only possible of course because Baowu steel is owned by the Chinese Government rather than private investors, who would surely divert the company's revenue into their own bank accounts rather than social welfare programs if given the chance. Of course these kinds of ‘Visible Hand’ solutions are off limits for somebody like Mr. Gates because those markets must remain “free” for him to exploit. If AGRA investors took an honest look at poverty alleviation in China they would be forced to admit that the ‘invisible hand’ of the market will simply not solve all society's problems, and in fact it is contributing to global issues like malnutrition in Africa. However, Mr. Gates and the other AGRA investors are not concerned with malnutrition in Africa and they never have been. They are exclusively concerned with their own bottom line. It is inconsequential to them whether or not people in Africa are lifted from poverty, so long as they are able to continue selling commodities in Africa. Do small African farmers not have enough money for our commodities? Give them predatory loans! Are the banks using the loans to make money off farmers and trap them in debt? They just need more fertilizer to make more crops and revenue! Is the fertilizer poisoning the soil? I really don’t care. Buy more Fertilizer! These are the only solutions we will ever get from private interests when it comes to poverty alleviation. They will never admit the market is not working. Because for them, the market is working! It’s allowing them to accumulate mass hoards of wealth and exploit entire continents. One of the last people who tried to bring some ‘visible hand’ economics to Africa was Libyan leader Mummar Gaddafi, who had plans to create a publicly owned African central development bank. For his efforts, Gaddafi was murdered by NATO at the beheast of Western Finance capitalists. Libya had one of the highest living standards in Africa under Gadaffi. After the intervention overseen by Hillary Clinton, Libya now has an open air slave market and has been torn apart by civil war. That is what Bill Gates and his cronies do to anybody who makes a real attempt to alleviate poverty in Africa. They lobby for and cheerlead murderous interventions while portraying themselves as the saviors of Africa, who are so generously abolishing poverty through their philanthropy. If the invisible hand of the market and the philanthropic efforts of wealthy investors fail to alleviate poverty as they promised? It's not because of capitalism or the market, it’s because the African population is too high and needs to be decreased! This is what happens when you have a society where public health decisions are determined by markets, multinational corporations, and Bill Gates. Or more simply, when society is dominated by the capitalist class. Under capitalism millions of people go without having their most basic needs met and charitable giving becomes a tool of colonialism. As Marx said “all that is holy is profaned” References Wilensky, S. E., & Teitelbaum, J. B. (2023). Chapter 2. In Essentials of health policy and law (4th ed., pp. 12–12). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning. Shapiro, N. (2022, September 8). Gates-funded 'green revolution' in Africa has failed, critics say. The Seattle Times. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/gates-funded-green-revolution-in-africa-has-failed-critics-say/ Wallace-wells, D. (2022, September 13). Bill Gates: 'we're in a worse place than I expected'. The New York Times. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/13/opinion/environment/bill-gates-climate-change-report.html Berezow, A. (2020, May 26). Irish Potato Famine: How belief in overpopulation leads to human evil. American Council on Science and Health. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://www.acsh.org/news/2020/05/14/irish-potato-famine-how-belief-overpopulation-leads-human-evil-14792 Tricontinental Institute for Social Research. (2021, July 23). Serve the people: The eradication of extreme poverty in China. Tricontinental. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://thetricontinental.org/studies-1-socialist-construction/#part3_poverty-alleviation-theory-and-practice AuthorEdward Liger Smith is an American Political Scientist and specialist in anti-imperialist and socialist projects, especially Venezuela and China. He also has research interests in the role southern slavery played in the development of American and European capitalism. He is a co-founder and editor of Midwestern Marx and the Journal of American Socialist Studies. He is currently a health care administration graduate student and wrestling coach at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. Archives September 2022 Friedrichstrasse, bisected by the Berlin Wall, in 1961. Operation Red Sox dropped 85 CIA agents into Soviet-controlled territory to gather intelligence about Moscow’s plans. [Source: politico.com] Joe Biden “is fueling the fire in the Ukraine.” It takes a musical artist to cut through the morass of propaganda to educate American mainstream media (MSM) about the Russia-Ukraine crisis and the roleof the United States in instigating that conflict for its own nefarious ends. The MSM have constructed an undiluted narrative about “Putin’s War” that disguises America’s imperialist expansion into eastern Europe. It is utterly Orwellian in its effort to project onto Russia what the U.S. and its main imperial ally, the UK (which a British journalist deemed “America’s tugboat”), have been doing non-stop since 1945—and indeed for centuries. Looking back, the U.S. under Truman began the policy of turning enemies (Germany, Japan) into friends and friends (the important war-time alliance with the USSR) into enemies. The CIA, established in 1947, was the main clandestine instrument of this policy, working closely with the neo-Nazi Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) to carry out acts to sabotage, divide and destabilize the Soviet state. OUN logo [Source: wikimedia.org] The OUN, in particular the faction led by the German ally Stepan Bandera and his second in command, Yaroslav Stetsko, OUN-B, was a violently anti-semitic, anti-communist, and anti-Russian organization, which collaborated with the Nazi occupation and actively participated in the slaughter of millions of Poles, Ukrainian Jews, and ethnically Russian and Ukrainian communists in the region. Nonetheless, The Washington Post treated Stetsko as a national hero, a “lonely patriot.” Yaroslav Stetsko with then-Vice President George H.W. Bush. [Source: fpif.org] The OUN-German alliance in 1941 was backed by the leaders of the Ukrainian Orthodox and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic churches. The latter’s archbishop, Andrey Sheptytsky, penned a pastoral letter that declared: “We greet the victorious German Army as deliverer from the enemy. We render our obedient homage to the government which has been erected. We recognize Mr. Yaroslav Stetsko as Head of State … of the Ukraine.”

Azov Battalion fighters with NATO flag at left and Nazi flag at right. [Source: wsws.org] As in the past, U.S. foreign policy is prepared to accommodate such sectors within its circle of allies. On December 16, 2021, a draft resolution of the UN General Assembly was listed as “Combating glorification of Nazism, neo-Nazism and other practices that contribute to fueling contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance.” It passed by a recorded vote of 130 in favor (mainly the Third World, constituting the large majority of the world’s population), 51 abstentions (mainly the EU, Australia, New Zealand and Canada), and two opposed, the two being Ukraine and the United States. The Western European countries that Hitler conquered and occupied would not condemn present-day manifestations of Nazism and fascism. Harry Truman, infamously declared as a senator in 1940 in response to Operation Barbarossa that “If we see that Germany is winning, we ought to help Russia and if Russia is winning we ought to help Germany and that way let them kill as many as possible.” This showed what little regard he had for the Russian and other Soviet people—which became more evident when he became president. During his tenure in the White House, the U.S. helped rebuild the industrial capacity of Western Europe (in large part to prevent communists and socialists from winning elections), but he also launched a war on North Korea, destroying virtually every structure in the country through bombing, including incendiary and napalm weapons. He initiated the Cold War, massively escalated the military budget, organized NATO, and used atomic weapons on civilian populations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in large part to block the allied Soviets from gaining territory in Japan in the last days of the war. Perhaps Truman’s most destructive initiative was the creation of the CIA, a monster that he later claimed got out of hand, telling a friend “I never would have agreed to the formulation of the Central Intelligence Agency back in forty-seven, if I had known it would become the American Gestapo, ”though as president he supported its clandestine activities in Eastern Europe. The immediate target was Soviet Ukraine, which the CIA hoped through its clandestine projects to “crack apart” with saboteurs behind enemy lines. President Harry S. Truman signing off on creation of the CIA. [Source: historydaily.org] Its task was a carry-over from the World War II covert action agency, the OSS, which had worked with partisan groups resisting the Nazi occupation. In Ukraine, the U.S. simply flipped the enemy by supporting Nazi insurgent organizations fighting the Soviet Union, the country that had just saved Europe from the scourge of Hitler’s Third Reich. The CIA’s plan, part of its “stay behind” operations in Central and Eastern Europe, was to airdrop Ukrainians from the ultra-nationalist groups, in particular OUN-B, that would involve the smuggling of weapons, the uses of covert communication transmissions, spies, commandos, banditry, assassins and sabotage. A declassified secret CIA history shows that the Agency refused to extradite the OUN war criminal Bandera to the Soviets in order to keep the underground movement and the destabilization efforts in Ukraine intact.