|

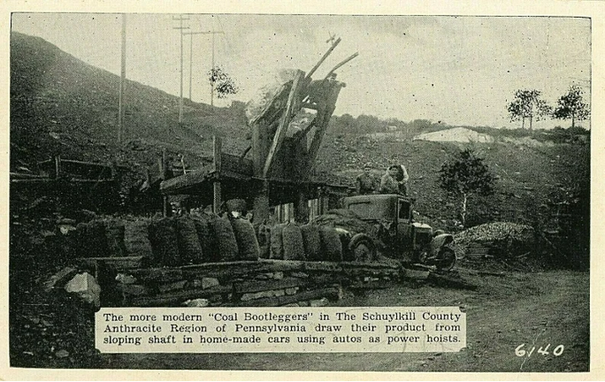

7/20/2022 Book Review: The Weather Makers: How Man is Changing the Climate and What it Means for Life on Earth-Tim Flannery. Reviewed By: Thomas Riggins (6/7)Read NowPart 6 Let’s look at just some of the problems we create by burning coal, according to the scientific evidence in Flannery's book. There are wee bits of dust and particulate matter that drifts in the atmosphere. They are called aerosols. Coal burning plants in the U.S. now pump so many aerosols into the atmosphere that they kill about 60,000 people per year in this country alone (increased mortality thru lung diseases). Lung cancer rates are higher around areas with coal burning plants. Aerosols also influence "global dimming." This is a phenomenon whereby less sunlight can reach the earth. Soot aerosols, along with jet trails, reflect sunlight back into space cooling the earth. But we are putting so much CO2 into the air that the heat being trapped is greater than the heat being reflected into space. Therefore the earth is warming up. The only thing that can prevent an ecological disaster is to start removing CO2 from the air (which we have not figured out how to do in any meaningful way). If we stopped putting CO2 into the air today the CO2 already there will continue to heat the earth for decades. So, we are facing a big problem. Here are some interesting statements from Flannery. It seems that if all new greenhouse gasses were immediately stopped from entering the air, the ones already in the air would continue to heat up the planet until 2050 or so. Then the atmosphere would stabilize at a new higher annual temperature. But we are no way near halting our polluting ways! In fact, we should note that "half the energy" we have burned since the beginning of the industrial revolution has been burned in just the last 20 years. So our polluting is becoming more intense. Here is what we have to do to stabilize the climate around 2100-- we would need to reduce CO2 by 70% of the 1990 level by 2050. Then we would have CO2 at 450 parts per million. Flannery thinks it more realistic to aim at 550 parts per million with climate stabilization "centuries from now." The earth would end up around 5.4 degrees F [or 3 C] hotter by 2100 than it is now. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change says we must prevent "dangerous" climate change. So what constitutes dangerous climate change? It seems the consensus is about 2 degrees C-- anything over that may lead to disaster. So 2C is the most we can stand for, and if we get to work NOW we may still get 3C by 2100, the outlook is not so hot (no pun intended). "Earth's average temperature," Flannery writes, "is around 59 degrees F, and whether we allow it to rise by a single degree or 5 degrees F will decide the fate of hundreds of thousands of species, and most probably billions of people." Besides oceans, rain forests and coral reefs, the world's mountains are also experiencing rapid change. You can forget the snows of Kilimanjaro and the glaciers of New Guinea. The CO2 already in the atmosphere has doomed them and they will be gone in just a few decades. As the earth warms the mountain habitat changes and animals who were lower down on the mountain move to the top while the topmost species go extinct. We are now in the process of losing mountain gorillas, panda bears and many plant species. Flannery says some species benefit from global warming. The Anopheles mosquito is spreading and the malaria parasites it spreads will soon be infecting "tens of thousands of people without any resistance to the disease." Obama's stimulus bill, whatever else it did, may have been a boon for malaria parasites. It contained one billion dollars for the coal industry to help develop "clean coal" [there is no such animal] which fostered the illusion that we can survive without closing down the coal industry itself. We can't save everything, but scientists think if we start taking strong action now we will ONLY lose one third of all existing species on earth. If we don't take action, then by 2100 we will have doomed 60% of existing species to extinction. Is burning coal and other fossil fuels really worth it? Don't think calculations have not been made. Economists working for the UN in conjunction with the World Meteorological Association have done calculations that concluded it was too expensive to really halt climate change. The rich nations will be able to deal with it. The billions of poor in the Third World will be the ones to suffer but, the economists calculated that the life of a poor person was "worth only a fifteenth of that of a rich person." It is just not cost effective, according to them, to try and save the poor. At this point I wish Flannery would refer to Marxism, but alas he seems not to be a Marxist. More grim news to come in part 7, the last part. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. He is the author of Reading the Classical Texts of Marxism. Archives July 2022

0 Comments

The West seems more fixated on spending social wealth on the military rather than addressing the climate catastrophe. During late April and early May, South Asia experienced the terrible impacts of global warming. Temperatures reached almost 50 degrees Celsius (122 Fahrenheit) in some cities in the region. These high temperatures came alongside dangerous flooding in Northeast India and in Bangladesh, as the rivers burst their banks, with flash floods taking place in places like Sunamganj in Sylhet, Bangladesh. Saleemul Haq, the director of the International Center of Climate Change and Development, is from Bangladesh. He is a veteran of the UN climate change negotiations. When Haq read a tweet by Marianne Karlsen, the co-chair of the UN’s Adaptation Committee, which said that “[m]ore time is needed to reach an agreement,” while referring to the negotiations on loss and damage finance, he tweeted: “The one thing we have run out of is Time! Climate change impacts are already happening, and poor people are suffering losses and damages due to the emissions of the rich. Talk is no longer an acceptable substitute for action (money!)” Karlsen’s comment came in light of the treacle-slow process of agreement on the “loss and damage” agenda for the 27th Conference of Parties or COP27 meeting to be held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in November 2022. In 2009, at COP15, developed countries of the world had agreed to a $100 billion annual adaptation assistance fund, which was supposed to be paid by 2020. This fund was intended to assist countries of the Global South to shift their reliance on carbon to renewal sources of energy and to adapt to the realities of the climate catastrophe. At the time of the Glasgow COP26 meeting in November 2021, however, developed countries were unable to meet this commitment. The $100 billion may seem like a modest fund, but is far less than the “Trillion Dollar Climate Finance Challenge,” that will be required to ensure comprehensive climate action. The richer states—led by the West—have not only refused to seriously fund adaptation but they have also reneged on the original agreements, such as the Kyoto Protocol (1997); the U.S. Congress has refused to ratify this important step toward mitigating the climate crisis. The United States has shifted the goalposts for reducing its methane emissions and has refused to account for the massive output of carbon emissions by the U.S. military. Germany’s Money Goes to War Not Climate Germany hosts the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In June, as a prelude to COP27, the UN held a conference in Bonn on climate change. The talks ended in acrimony over finance for what is known as “loss and damage.” The European Union consistently blocked all discussions on compensation. Eddy Pérez of the Climate Action Network, Canada, said, “Consumed by their narrow interests, rich nations and in particular countries in the European Union, came to the Bonn Climate Conference to block, delay and undermine efforts from people and communities on the frontlines addressing the losses and damage caused by fossil fuels.” On the table is the hypocrisy of countries such as Germany, which claims to lead on these issues, but instead has been sourcing fossil fuels overseas and has been spending increasing funds on their military. At the same time, these countries have denied support to developing countries facing devastation from climate-induced superstorms and rising seas. After the recent German elections, hopes were raised that the new coalition of the Social Democrats with the Green Party would lift up the green agenda. However, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has promised €100 billion for the military, “the biggest increase in the country’s military expenditure since the end of the Cold War.” He has also committed to “[spending] more than 2 percent of the country’s gross domestic product on the military.” This means more money for the military and less money for climate mitigation and green transformation. The Military and Climate Catastrophe The money that is being swallowed into the Western military establishments does not only drift away from any climate spending but also promotes greater climate catastrophe. The U.S. military is the largest institutional polluter on the planet. The maintenance of its more than 800 military bases around the world, for instance, means that the U.S. military consumes 395,000 gallons of oil daily. In 2021, the world’s governments spent $2 trillion on weapons, with the leading countries being those who are the richest (as well as the most sanctimonious on the climate debate). Money is available for war but not to deal with the climate catastrophe. The way weapons have poured into the Ukraine conflict gives many of us pause. The prolongation of that war has placed 49 million more people at risk of famine in 46 countries, according to the “Hunger Hotspots” report by the United Nations agencies, as a result of the extreme weather conditions and due to conflicts. Conflict and organized violence were the main sources of food insecurity in Africa and the Middle East, specifically in northern Nigeria, central Sahel, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan, Yemen and Syria. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated the food crisis by driving up the price of agricultural commodities. Russia and Ukraine together account for around 30 percent of the global wheat trade. So, the longer the Ukraine war continues, the more “hunger hotspots” will grow, taking food insecurity beyond just Africa and the Middle East. While one COP meeting has already taken place on the African continent, another will take place later this year. First, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, hosted the UN Convention to Combat Desertification in May and then Sharm el-Sheikh will host the UN Climate Change Conference. These are major forums for African states to put on the table the great damage done to parts of the continent due to the climate catastrophe. When the representatives of the countries of the world gather at Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, in November 2022 for COP27, they will hear Western representatives talk about climate change, make pledges, and then do everything possible to continue to exacerbate the catastrophe. What we saw in Bonn is a prelude to what will be a fiasco in Sharm el-Sheikh. AuthorMurad Qureshi is a former member of the London Assembly and a former chair of the Stop the War Coalition. This article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives July 2022 7/18/2022 Christianity Marxism and the Death of Reason in the Ancient World. By: Thomas RigginsRead NowCharles Freeman’s The Closing of the Western Mind is a great introduction to the origins of Christian thought. Today, with so many competing versions of Christianity, ranging from traditional Orthodox and Catholic views to liberal socially conscious Protestantism and right-wing evangelical fundamentalism, it is helpful to have a guide such as this which explains, supplemented by a Marxist outlook, how the original Christianity of the ancient world came about. Freeman will do a credible job of tracing this history from Roman times to the High Middle Ages. In his Introduction he tells us that he will be dealing with ‘’a significant turning point’’ in Western civilization. The point he has in mind is that time in the fourth and fifth centuries AD “when the tradition of rational thought established by the Greeks was stifled.” It would take the West a thousand years to recover. The Greek rational tradition was firmly established by the fifth century BC — its two greatest founders were Plato and his student Aristotle. Unfortunately, Freeman confuses modern day empiricism with rationality and misapprehends the significance of Plato, following in the footsteps of his master Socrates, in the establishment of the rational method in Greece. Plato’s thought was not “an alternative to rational thought” but one of the most extreme examples of it, subjecting all beliefs to the test of logical argument whenever possible. Be that as it may, Freeman thinks that the Greek rational tradition, today’s term would be “scientific,” was deliberately squashed by the Roman government from the time of Constantine with the aid of the official church. The wide-open intellectual environment of the Roman Empire, both religiously and philosophically, came to an end in the 4th century when the Emperor Constantine made Christianity the “official” state religion. The “official” version became the only legal version and thus was the “orthodox” version, “The imposition of orthodoxy,” Freeman writes, “Went hand in hand with the stifling of any form of independent reasoning.” Christianity was from the onset anti-rational. Freeman writes, “ It had been the Apostle Paul who declared war on the Greek rational tradition through his attacks on ‘the wisdom of the wise’ and ’the empty logic of the philosophers’ …” When Christianity became the official creed it closed down any contrary thinking thus dooming the West to a thousand yeas of backwardness. A good example of this mind closing is given by Freeman when he discusses the dispute between St. Ambrose and the traditional Roman senator Quintus Aurelius Symmachus. To my way thinking Symmachus had an open modern mind while Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan and teacher of S. Augustine, was a bigot. “In the late fourth century the seat of the Western Empire was in Milan and there were still many pagans (believers in the old traditional religion) who wished to be free to continue their form of religion. The Christian authorities were determined to repress all forms of religion save their own. One of the major symbols of the traditional religion was the Altar of Peace which adorned the Senate in Rome. The Christians had it removed in 383 AD. Symmachus and other senators petitioned the Emperor to have it restored. Ambrose (a major power behind the throne) was opposed and the petition failed. The mindsets of the two sides are clearly expressed in the following written exchange.” “Symmachus: ‘What does it matter by which wisdom each of us arrives at the truth? It is not possible that only one road leads to so sublime a mystery.’ Ambrose: ‘What you are ignorant of, we know from the word of God. And what you try to infer, we have established as truth from the very wisdom of God’” The Truth, however, should be able to triumph without the aid of the rack and the stake. Paul himself had no personal knowledge of Jesus in the flesh. Freeman asserts that the intolerance of the Christians (their rejection of logic and science) stems from Paul. What is worse, when, for political reasons the Roman state adopted the religion and forced it upon everyone, its motive was to control the minds of the population for the benefit of the empire. The actual teachings of Jesus were no more suited to the ends desired by the Romans than they are to the actions of US imperialism today and the fundamentalist and evangelicals who blindly support it in the name of patriotism. Paul, according to Freeman, distanced himself from the original 12 disciples (who distrusted his claims) and ended up, as we know, creating a theology that appealed to the Greco-Roman world and was rejected by the Jewish community from which Jesus came. In order to do this the real “historical” Jesus and his teachings (peace not war, forgiveness not vengeance, love and respect, not hatred and contempt— i.e., Martin Luther King, Jr, not Jerry Falwell nor Pat Robinson) had to be replaced with an unreal Christ beyond history. Thus, Freeman writes, “Paul makes a point of stressing that faith in Christ does not involve any kind of identification with Jesus in his life on earth but has validity only in his death and resurrection.” Thus the burden of actually having to follow the particular ethical path that Jesus the human trod is removed. [What is called “Christianity” today ought rather to be called “Paulism.”] Since the claims made for Jesus as the Christ are simply impossible to accept from the point of view of reason, reason is dumped and is replaced by “faith.” Freeman gives the following quote from the fourth century ascetic Anthony: “Faith arises from the disposition of the soul, those who are equipped with the faith have no need of verbal argument.” It is also interesting note, as Freeman does, that Anthony was claimed not to have learned ‘to read or write, the point being made by his biographer that academic achievement was not important for ‘a man of God’ and could even be despised.”… achieving a fill identification Freeman is incorrect, I think, in holding that the personal commitment Christians made to Christ (becoming “a single body with Christ through his death and then rising with him from the dead”) was “something new in antiquity.” This very belief was characteristic of the devotees of the Egyptian god Osiris whose worship in the cult of Isis and Osiris was widespread throughout the Roman Empire and whose popularity may explain why Christianity proved to be so popular to the Greco-Roman population. Mary idolatry, still rampant in some forms of Christianity, may have stemmed from this cult connection as well. Freeman points out that Isis was the patron goddess of mariners and her symbol was the rose. Mary replaced her as the patroness of sailors and her symbol was also the rose. He also writes, “representations of Isis with her baby son Horus on her knee seem to provide the iconic background for those of Mary and the baby Jesus.” The Greek rational tradition demanded that people think for themselves and take responsibility for their actions. Christianity introduced a different conception of moral responsibility. It introduced the idea of “don’t think, just follow orders.” Freeman quotes long extract from William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, in which a Jesuit explains the value of living the monastic life (every religion has something similar to this as well as some political groups on the left as well as the right). The Jesuit explains that if you obey the orders of your religious superior, no matter what they are, you can do no wrong! “The Superior may commit a fault in commanding you to do this or that, but you are certain that you commit no fault as long as you obey, because God will only ask you if you have duly performed what orders you received …. The moment what you did was done obediently, God wipes it out of your account….” Nice! Not even God respects the Geneva Conventions, why should the U.S. or anyone else? “Here the abdication to think for oneself is complete. The book clearly demonstrates that religion in the West has been used to deprecate and reject reason (unless the church can misuse it in its own interests). It also demonstrates that in the modern world ,the progressive part at any rate, represents a return to the Greek outlook. When Freeman, in reference to the teachings of the church, writes”The ancient Greek tradition that one should be free to speculate without fear and be encouraged to take individual moral responsibility for one’s views was rejected,” we can today assert that now in the 21st century, despite the tragic history of”real existing socialism” in the past century, no genuine Marxist committed to genuine people’s democracy would agree with the church on this matter. The most important internal reason for the collapse of the socialist block, I think, may have been the lack of real participatory democracy and citizen involvement. Traditional Christianity as well as fundamentalism may likewise now be facing this malaise which is also characteristic of American and other bourgeois “democracies, as well as some contemporary so-called Marxist groups which have learned nothing from the past. What Freeman writes about the Church can be extended to these other groups as well. “Intellectual self confidence and curiosity which lay at the heart of the Greek achievement, were recast as the dreaded sin of pride. Faith and obedience to the institutional authority of the church were more highly rated than the use of reasoned thought. The inevitable result was intellectual stagnation.” Reading Freeman’s well written and interesting book will give you a great background and a deep historical understanding as to how Christianity came to dominate the Western world for over a thousand years, and what that has cost in terms of intellectual degradation, and how, if the peoples of the West are to better their condition in this new century they must regain the intellectual confidence so characteristic of Greek civilization. I would maintain that the Marxist tradition, freed from the failed authoritarian models of the last century, is the best contemporary intellectual tool to achieve this end. But it is important to note that the Greeks were not the only people to have a rational outlook. Similar thinkers can be found in the “classical” periods of other cultures such as Ancient Egypt, China, India, and the Islamic culture of the Middle, to name but four, and the hope of a progressive future rests on a blending of the best progressive tendencies of all cultures. AuthorThomas Riggins is a retired philosophy teacher (NYU, The New School of Social Research, among others) who received a PhD from the CUNY Graduate Center (1983). He has been active in the civil rights and peace movements since the 1960s when he was chairman of the Young People's Socialist League at Florida State University and also worked for CORE in voter registration in north Florida (Leon County). He has written for many online publications such as People's World and Political Affairs where he was an associate editor. He also served on the board of the Bertrand Russell Society and was president of the Corliss Lamont chapter in New York City of the American Humanist Association. Archives July 2022 A newcomer to politics would likely assume that members of the global left support the People’s Republic of China. It is after all led by a communist party, with Marxism as its guiding ideology. During the period since the Communist Party of China (CPC) came to power in 1949, the Chinese people have experienced an unprecedented improvement in their living standards and human development. Life expectancy has increased from 361 to 772 years. Literacy has increased from an estimated 20 percent3 to 97 percent.4 The social and economic position of women has improved beyond recognition (one example being that, before the revolution, the vast majority of women received no formal education whatsoever, whereas now a majority of students in higher education institutions are female).5 Extreme poverty has been eliminated.6 China is becoming the pre-eminent world leader in tackling climate change.7 Such progress is evidently consistent with traditional left-wing values; what typically attracts people to Marxism is precisely that it seeks to provide a framework for solving those problems of human development that capitalism has shown itself incapable of satisfactorily addressing. Capitalism has driven historic innovations in science and technology, thereby laying the ground for a future of shared prosperity; however, its contradictions are such that it inevitably generates poverty alongside wealth; it cannot but impose itself through division, deception and coercion; everywhere it marginalises, alienates, dominates and exploits. Seventy years of Chinese socialism, meanwhile, have broken the inverse correlation between wealth and poverty. Even though China suffers from high levels of inequality; even though China has some extremely rich people; life for ordinary workers and peasants has continuously improved, at a remarkable rate and over an extended period. Yet support for China within the left in countries such as Britain and the US is in fact a fairly marginal position. The bulk of Marxist groups in those countries consider that China is not a socialist country; indeed many believe it to be “a rising imperialist power in the world system that oversees the exploitation of its own population … and increasingly exploits Third World countries in pursuit of raw materials and outlets for its exports.”8 Some consider the China-led Belt and Road Initiative to be an example of “feverish global expansionism”.9 The Alliance for Worker’s Liberty, with characteristic crudeness, describe China as being “functionally little different from, and in any case not better than, a fascist regime,”10 every bit as imperialist as the US and politically much worse. The growing confrontation between the US and China is not, on these terms, an attack by an imperialist power on a socialist or independent developing country, but rather “a classic confrontation along imperialist lines”.11 “The dynamics of US-China rivalry is an inter-imperial rivalry driven by inter-capitalist competition.”12 The assumption here is that China is “an emerging imperialist power that is seeking to assert itself in a world dominated by the established imperialist power of the US”.13 If that is the case, those that ground their politics in anti-imperialism should not support either the US or China; rather they should “build a ‘third camp’ that makes links and solidarity across borders”14 and adopt the slogan Neither Washington nor Beijing, but international socialism.” It’s an attractive idea. We don’t align with oppressors anywhere; our only alignment is with the global working class. Eli Friedman eloquently presents this grand vision in the popular left-wing journal Jacobin: “Our job is to continually and forcefully reaffirm internationalist values: we take sides with the poor, working classes, and oppressed people of every country, which means we share nothing with either the US or Chinese states and corporations.”15 We’ve been here before: Neither Washington nor MoscowThis notion of opposing both sides in a cold war – refusing to align with either of the two major competing powers and instead forming an independent ‘third camp’ – has deep roots. Prominent US Trotskyist Max Shachtman described the third camp in 1940 as “the camp of proletarian internationalism, of the socialist revolution, of the struggle for the emancipation of all the oppressed.”16 During the original Cold War, in particular in Britain, a significant proportion of the socialist movement rallied behind the slogan Neither Washington nor Moscow, withholding their support from a Soviet Union they considered to be state capitalist and/or imperialist. Then as now, the third camp position drew theoretical justification from the strategy promoted by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in relation to World War 1. The communist movement in the early 1910s recognised that a war between the two major competing imperialist blocs (Germany on one side, and Britain and France on the other) was near-inevitable. At the 1912 conference of the Second International in Basel, the assembled organisations vowed to oppose the war, to refuse to align themselves with any component part of the international capitalist class, and to “utilise the economic and political crisis created by the war to arouse the people and thereby to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule.”17 Rather than rallying behind the German, British, French or Russian ruling classes, workers were called on to “oppose the power of the international solidarity of the proletariat to capitalist imperialism.” When war eventually broke out in July 1914, the Bolsheviks stuck to this internationalist position. Lenin wrote regarding the warring imperialist blocs: “One group of belligerent nations is headed by the German bourgeoisie. It is hoodwinking the working class and the toiling masses by asserting that this is a war in defence of the fatherland, freedom and civilisation, for the liberation of the peoples oppressed by tsarism… The other group of belligerent nations is headed by the British and the French bourgeoisie, who are hoodwinking the working class and the toiling masses by asserting that they are waging a war for the defence of their countries, for freedom and civilisation and against German militarism and despotism.”18 Further: “Neither group of belligerents is inferior to the other in spoliation, atrocities and the boundless brutality of war; however, to hoodwink the proletariat … the bourgeoisie of each country is trying, with the help of false phrases about patriotism, to extol the significance of its ‘own’ national war, asserting that it is out to defeat the enemy, not for plunder and the seizure of territory, but for the ‘liberation’ of all other peoples except its own.” However, the majority of the organisations that had signed up to the Basel Manifesto just two years earlier now crumbled in the face of pressure, opting to support their ‘own’ ruling class’s war efforts. Lenin condemned the prominent Marxist leaders in Germany, Austria and France for holding views that were “chauvinist, bourgeois and liberal, and in no way socialist.”19 This bitter strategic dispute was a catalyst to a split in the global working class movement. The Second International was disbanded in 1916, and the Third International (widely known as the Comintern) was established in 1919 with its headquarters in Moscow. A century later this rift – described by Lenin in his famous article Imperialism and the Split in Socialism20 – remains a fundamental dividing line in the international left. Broadly speaking, one side consists of a reformist left inclined towards parliamentarism and collaboration with the capitalist class; the other side consists of a revolutionary left inclined towards an independent, internationalist working class line. The theorists of Neither Washington nor Moscow in the 1940s insisted that the Cold War was analogous to the European inter-imperialist conflict of the 1910s; that the US-led bloc and the Soviet-led bloc were competing imperialist powers and that it was impermissible for socialists to ally with either of them. The characterisation of the Soviet Union as imperialist was highly controversial within the global left at the time, but prominent socialist thinkers led by Tony Cliff of the Socialist Review Group (the precursor to the Socialist Workers Party) argued strongly that “the logic of accumulation and expansion” drove the Soviet leadership to take part in “external global military competition”.21 Given Soviet imperialism and state capitalism, “nothing short of a socialist revolution, led by the working class, would be able to transform this situation”.22 The third camp has apparently survived the storm generated by the collapse of the Soviet Union and simply pitched its tent a few thousand kilometres southeast; Neither Washington nor Moscow has reappeared as Neither Washington nor Beijing. Once again invoking the spirit of the Bolsheviks, several prominent left organisations call on the working class in the West to oppose both the US and China; to fight imperialism in all its forms; to support workers’ struggle everywhere to bring down capitalism. If their assumptions are correct – if the New Cold War is indeed analogous to the situation prevailing in Europe before WW1, if China is an imperialist country, if the Chinese working class is ready to be mobilised in an international revolutionary socialist alliance – then perhaps their conclusion is also correct. I argue in this article that the assumptions are not correct, that China is not an imperialist country, that China is in fact a threat to the imperialist world system, and that the correct position for the left to take in regard to the New Cold War is to resolutely oppose the US and to support China. Is China imperialist?The position of opposing both the US and China relies mainly on the premise that China is imperialist, and that the New Cold War is an inter-imperialist war – a war in which “both belligerent camps are fighting to oppress foreign countries or peoples”23. If China can be shown not to be an imperialist power, and if the New Cold War can be shown not to be an inter-imperialist struggle, then the slogan Neither Washington nor Beijing should be rejected. What is imperialism? One definition is “the policy of extending the rule or authority of an empire or nation over foreign countries, or of acquiring and holding colonies and dependencies.”24 Although vague, this incorporates the core concept of empire, hinted at by the word’s etymology. In his classic work Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism – the first serious study of the phenomenon from a Marxist perspective – Lenin states that, reduced to its “briefest possible definition”, imperialism can be considered simply as “the monopoly stage of capitalism”.25 Lenin notes that such a concise definition is necessarily inadequate, and is only useful to the extent that it implies the presence of five “basic features”: