|

2/20/2022 Elections in Colombia: Prospects for Change and Lack of Guarantees. By: Lautaro RivaraRead NowWith legislative and presidential elections coming up in Colombia, the supposedly “oldest democracy in Latin America” will see if it can consolidate the most precarious and recent peace on the continent. The Latin American and Caribbean electoral calendar for 2022 promises to be no less hectic than that of the previous year. Among the upcoming elections and referendums that are slated for this year—Costa Rica, Mexico, Chile, Peru, perhaps Haiti—two contests that are expected to attract the most attention, due to the specific geopolitical weight of these respective countries, are the general elections in Brazil, which are supposed to take place in October, and the Colombian parliamentary and presidential elections, slated for the first half of 2022. After 20 years of governments that have supported the Uribism movement—named after Álvaro Uribe Vélez, who was president of Colombia from 2002 to 2010—and with the eternal backdrop of the armed conflict, Colombia is not only playing for change but also for the future of an unfinished peace process. What Will the Electoral Process in Colombia Look Like? The electoral agenda in Colombia will begin with the parliamentary election on March 13, in which citizens will have to elect a total of 108 senators and 188 members of the House of Representatives. In the Senate, 100 seats will be chosen by national constituency; two by the special constituency for Indigenous peoples; one will go to the presidential candidate who gets the second-highest number of votes—the so-called “opposition statute”; and five will automatically correspond to the political representation of the Comunes party—which was created in 2017 by members of the former FARC party (Common Alternative Revolutionary Force) following the 2016 Havana peace accords. As for the House of Representatives, 161 seats will be elected by territorial constituencies in the 32 departments of the country and in Bogota, the capital district. One seat will go to the vice presidential candidate who receives the second-most votes under the opposition statute; two will go to Afro-Colombian peoples; one will be for the Raizal community of the archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina; one will go to Colombians living abroad—estimated to be around 4.7 million people according to the 2012 figures provided by Colombia’s Foreign Ministry; one seat will be for Indigenous peoples; five seats will again be for the Comunes party; and 16 seats will be for the special constituency for peace, by which 167 rural municipalities will participate to elect candidates who will represent the 9 million victims of the internal armed conflict officially recognized by the state. In addition, coinciding with the parliamentary election on March 13, the various parties in Colombia will also elect the presidential candidates during the internal consultations of the coalitions that will go to the polls, in a scheme that seems to increasingly blur the traditional liberal-conservative bipartisan scheme present throughout Colombian history. Elections for the positions of president and vice president, both of whom will hold office until 2026, will take place on May 29. If no ticket wins more than 50 percent of the votes, there will be a second round of voting on June 19. The Crisis of Uribism and the Favoritism of the Historic Pact In Parliament, the ruling Democratic Center, which is the party formed by former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe Vélez, could lose its present first minority in the Senate, with 19 seats, and second minority in the House, with 32, due to the high disapproval ratings for President Iván Duque (whose disapproval ratings reached 75 percent, according to an Invamer survey of September 2021) and for his mentor Uribe (who had a disapproval rating of 68 percent). The latter is accused of being responsible for a notorious case of witness tampering that led to a judge placing him under house arrest for two months in August 2020. And he has also been associated with the “alleged electoral corruption” scandal also called “ñeñepolítica,” according to which the renowned drug trafficker José “Ñeñe” Guillermo Hernández had contributed drug money for the purchase of votes in the 2018 presidential election in Colombia, as was revealed by journalists Julián Martínez and Gonzalo Guillén of La Nueva Prensa. But the fact that best explains the electoral panorama in Colombia, which was unthinkable just a couple of years ago, is the national strike of 2021, accompanied by a series of massive protests in rural areas and in some of the main cities of the country, such as Bogotá and Cali, in rejection of the tax reform bill presented by Duque. The escalation of repression by the Armed Forces, the ESMAD (Colombia’s Anti-Disturbance Mobile Squadron) and even the deployment of paramilitary groups in several departmental capitals contributed to the crisis and provided visibility to these protests at the international level. According to the nonprofit organization Temblores—which “[documented] practices of police violence” during the national strike in Colombia—between April 28 and June 26, 2021, there were 44 homicides allegedly at the hands of the security forces (another 29 homicides remained undetermined with regard to the exact cause of death); 1,617 victims of physical violence; 82 cases of violence resulting in eye injuries to the victims; 28 victims of sexual violence; and 2,005 arbitrary detentions against the demonstrators. Providing varying figures, Human Rights Watch, Indepaz and the Ombudsman’s Office, along with other nonprofits and agencies, also validated the numerous cases of human rights violations during the demonstrations that took place in Colombia. In the midst of this crisis, and after a long dance of seduction and rejection with the right wing that was not associated with Uribe, the candidate chosen by the ruling party, former Minister of Finance Óscar Iván Zuluaga, stated in January 2022 that he will run alone on behalf of the Democratic Center, a move that will most likely diminish the electoral prospects of the Democratic Center. In addition to the governing party, there will be three other coalitions that will “aim to define single candidates among different political forces” on March 13. From the left to the center-left is the Historic Pact Coalition, which brings together “presidential pre-candidates,” such as former mayor of Bogotá Gustavo Petro for the Colombia Humana and Afro-Colombian social leader Francia Márquez for the Soy Porque Somos (“I am because we are”) movement. Other “political movements” that form part of the Historic Pact Coalition are Patriotic Union—a party that has survived the “genocide for political reasons” of more than 5,000 of its militants and leaders in the 1980s; the Colombian Communist Party; the Alternative Democratic Pole; the Indigenous and Social Alternative Movement (MAIS); the People’s Congress; and the party of former Congresswoman Piedad Córdoba, Movimiento Poder Ciudadano, among others. Even figures who used to be part of Uribe’s Democratic Center party, such as Roy Barreras and Armando Benedetti, have come out in support of the Historic Pact. Few doubts remain about the favoritism of Petro, the coalition’s main builder, who started his electoral campaign on January 14 in the locality of Bello, in the department of Antioquia—a historic bastion of Uribism—under the slogan “if Antioquia changes, Colombia changes.” Petro, a former militant of the guerrilla group known as the April 19 Movement in the 1970s and 1980s, built his political capital as a senator when he was elected in 2006 and as a denouncer of the so-called “parapolitics”—the collusion of politicians and paramilitaries during the demobilization process of the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC)—during Uribe’s first term as president. Petro revalidated his capital later, in his tenure as mayor of Bogotá, until his removal by Attorney General Alejandro Ordóñez in 2013, in one of the region’s first lawfare cases. As a presidential candidate, Petro received promising poll numbers from Invamer: 48.4 percent of voting intention, very close to victory in the first round, and a comfortable 68.3 percent in the second round. In second place is a centrist group, the Hope Center Coalition, which includes the Dignity Party, the Revolutionary Independent Labor Movement or MOIR, New Liberalism and Citizens’ Commitment, the party of the best-positioned candidate of the coalition, the former mayor of Medellín and former governor of Antioquia, Sergio Fajardo. Lastly, and to the right of the political spectrum, is the Coalición Equipo por Colombia (Team for Colombia), a league of former mayors and governors of conservative orientation. The coalition consists of Creemos Colombia, the party of the former mayor of Medellín Federico Gutiérrez; País de Oportunidades, the party of Alejandro Char, the powerful politician and businessman of Syrian and Lebanese descent who was formerly the governor of Atlántico and mayor of Barranquilla, in Colombia’s Caribbean coast region; the Partido de la U, who declined the candidacy of its president Dilian Francisca Toro and will support the former mayor of Bogotá Enrique Peñalosa; and finally, with less competitive candidacies, the traditional Colombian Conservative Party and the MIRA Movement Party. The Armed Conflict and the Absence of Political and Electoral Guarantees Due to the multicultural approach of the pioneering 1991 Constitution, Colombian electoral law provides for special ethnic representations, according to local considerations. In addition to the political and economic exclusion of Indigenous, Black, Afro-Colombian, Raizal and Palenquero communities, and the postponement in the inclusion of entire regions in Colombia, such as the Pacific, the Orinoco and the Colombian Amazon, there is an urgent need for the representation of victims and former combatants of a conflict that only seems to be worsening, despite the partial and formal achievement of peace five years ago under the Havana peace accords. The worst consequences of the “decades of conflict” in Colombia have been the death of more than 600 social leaders and human rights defenders since the Havana agreements, according to the 2020 figures provided by the United Nations; the 6,402 so-called “false positives,” a state crime that involved the murder of civilians presented as guerrillas killed in combat; the continued armed activity of FARC dissidents, the National Liberation Army (ELN) and, above all, of numerous paramilitary formations such as the Gulf Clan; the more than 90 massacres committed in 2021 and 14 massacres that have been reported so far this year, according to the Institute of Development and Peace Studies (Indepaz); and, finally, the rising tensions on the Colombian-Venezuelan border, particularly in the Colombian departments of Norte de Santander and Arauca. In the latter area, the Ombudsman’s Office established that 33 people were killed and 170 families were displaced by the actions of irregular groups. The continuity of the conflict in Colombia, and the fact that the so-called “anti-subversive” policy has historically been the main workhorse of Uribism, explain some of the uncertainty that governs the Colombian political and electoral panorama. The same happens in relation to electoral guarantees, as seen during the allegations of fraud and vote-buying in 2018. And even in relation to the personal safety of the candidates, considering the death threats that the paramilitaries of the Águilas Negras-Bloque Capital made to Petro on December 4, 2021, or to the contemporary history of a country in which, in the last century alone, seven presidential candidates have been assassinated. It remains to be seen if arguably the “oldest democracy in Latin America” can, in the times to come, manage to consolidate the most precarious and recently achieved peace in the continent. AuthorLautaro Rivara is a sociologist, researcher and poet. As a trained journalist, he participated as an activist in different spaces of communications work, covering tasks of editing, writing, radio broadcasts, and photography. During his two years in the Jean-Jacques Dessalines Brigade in Haiti he was responsible for communications and carried out political education with Haitian people’s movements in this area. He writes regularly in people’s media projects of Argentina and the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean including Nodal, ALAI, Telesur, Resumen Latinoamericano, Pressenza, la RedH, Notas, Haití Liberte, Alcarajo, and more. Find him on Twitter @LautaroRivara. This article was produced by Globetrotter. Archives February 2022

0 Comments

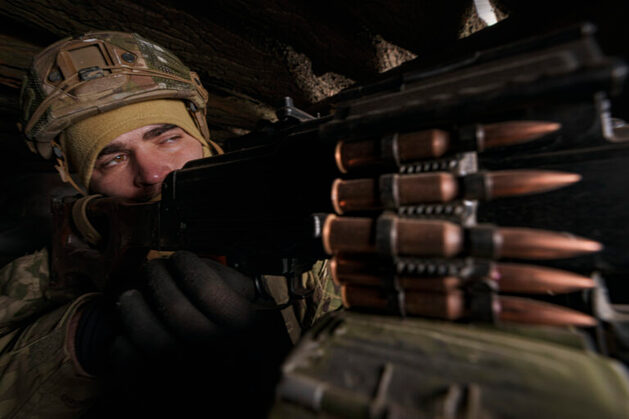

2/20/2022 Russian Communist leader: The West is backing fascists and using Ukraine. By: Gennady ZyuganovRead NowCommunist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov speaks at a news conference in Moscow. The CPRF Zyuganov leads has pushed a resolution through the Russian parliament urging the government to recognize the independence of the Russian-speaking breakaway Donetsk and Lugansk People's Republics in eastern Ukraine. | Pavel Golovkin / AP EDITOR’S NOTE: The following article is an edited version of an opinion piece written by Gennady Zyuganov, leader of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation. It was published on Feb. 14, 2022, the day before the State Duma, Russia’s Parliament, voted on a CPRF resolution calling on the government to officially recognize the independence of the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Lugansk People’s Republic. In recent weeks, the situation around Ukraine has sharply escalated. There are accusations of Russia’s intention to act as an occupier. In fact, the cause of the crisis is that the Washington puppeteers of the Kiev leadership and the fascist forces there are persistently trying to organize a massacre in the Donbass region. For the sake of solving their geopolitical tasks, they are ready to arrange another large-scale bloodshed.

The Pentagon and even the leadership of the Armed Forces of Ukraine declare that they see no signs of impending aggression from Russia. American intelligence, having lived through the shame of lies about the presence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, does not seem to want a new humiliation. But this does not stop Western politicians who habitually ignore the obvious: A “hybrid war” is being continued against Russia using lies, fraud, and disinformation. Yes, Russia has interests concerning the former Soviet republics on its borders, including Ukraine. These are the interests of peace and good neighborliness, a calm and dignified life for citizens, economic development, and cultural cooperation. Meanwhile, the West has demonstrated its readiness to rely on the most reactionary circles to pursue its interests. The predecessors of the current fascist groups in Ukraine—Stepan Bandera’s Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which collaborated with Hitler—are directly guilty of the genocide of the Russian, Belarusian, and their own peoples. It was their punitive detachments that carried out the most brutal reprisals against the population of the partisan regions of Belarus during the Great Patriotic War [World War II], burning the inhabitants of hundreds of villages alive. Today, their vile successors in the fascist organizations inside the Ukrainian army, with their aggressive Russophobia and anti-Semitism, are welcomed by Western politicians. More than 600,000 residents of the DPR and LPR have already received citizenship of the Russian Federation. Our country is directly responsible for their safety and lives. We cannot allow any fascist reprisal against these people. Russia has already seen enough of these deeds. As a result of the barbaric shelling of cities and villages of the DPR and LPR, more than 15,000 civilians have been killed. Tens of thousands of men and women, the elderly, and children were injured. Hundreds of thousands became refugees. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation and our allies have firmly defined our political line in this situation…. We firmly know that the peoples of Russia and Ukraine do not want a war. Such a war would also run counter to the fundamental interests of Europe. But the ruling powers of the United States appear to want it. Washington has been defeated in every war in recent decades. Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan are just some of the countries in which the United States has unleashed wars and ingloriously lost. This time, its leaders are eager to fight by proxy in Ukraine. The Washington “hawks” have set out to turn Ukrainians into cannon fodder. Political cover, the supply of weapons, the activities of Western military instructors—all this openly pushes the authorities in Kiev toward a bloody military adventure.

U.S. imperialists’ task is not to protect Ukraine, but to crawl out of the acute crisis of capitalism. It is extremely important for them to score new profits by torpedoing the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline [between Germany and Russia] and hooking the EU economy on the needle of expensive liquefied natural gas from the U.S. This is part of the true rationale behind the current military crisis in Ukraine. Russia is finally moving away from the pernicious idolatry of the West…. It’s time to show our character in the Donbass. We are surrounded by a chain of unfriendly states. It is impossible to retreat further. The West must feel Russia’s determination to defend itself and its friends. Of course, only a fundamental change in the path of Russia’s development will ensure a truly effective protection of the rights of the broad masses of the people in our country. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation does not accept the ongoing socio-economic course of the Putin government and offers the working people a program of transformation and a path toward socialist revival. But there are also issues that need to be addressed immediately.